The 2013 federal Open Payments legislation, which requires pharmaceutical companies to disclose their direct payments to physicians, was expected to help counter the corrupting influence of such payments. If the payments became public, the thinking went, medical school faculty would shy away from serving as the named authors on ghostwritten papers reporting clinical trial results, and they would refrain from being paid to give promotional talks as companies built markets for their newly approved drugs.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently published the 2020 payments, and thus there is now a seven-year record of payments that can be easily accessed. A Mad in America investigation of these records reveals that while the legislation has indeed reduced the participation of academic psychiatrists in these activities, the corrupting influence of pharmaceutical money on all phases of the drug development process—the testing of drugs, the reporting of results in journals, and the selling of newly approved drugs to the medical community—is ever-present. The corruption today is more entrenched than ever.

In psychiatry, there now exists what could be described as a psychopharmacology service industry, which can be divided into three sectors. There are a small number of academic psychiatrists who serve as consultants and advisors to companies as they run their phase II and phase III trials, and, together with company employees, serve as authors on the published reports of those studies. There is a second, somewhat larger group of psychiatrists who write further reviews of the phase II and phase III results, and by doing so help promote increased awareness of the new drugs. The third sector helps market the drugs to prescribers. Psychiatrists from the first two groups speak at conferences and serve as “faculty” for continuing medical education courses, and their efforts are complemented by a much larger number of community psychiatrists that populate the dinner circuit.

The most remarkable result of the Open Payments legislation is that the pharmaceutical companies are no longer attempting to hide this financial influence. The face of commerce is visible at every stage of the process: the biased design of the trials, the spinning of the results, and the subsequent touting of the drugs to prescribers. Thanks to the Open Payments database, the amount of money flowing to psychiatrists at each stage can now be reported.

There are two parts to this MIA investigation. The first part reviews the corruption that led Congress to pass the Open Payments legislation, and then details the flow of money to psychiatrists that can be gleaned from this database. The second part looks at how this commercial process was present in the testing and marketing of seven new psychotropic drugs that were approved by the FDA from 2013 to 2017, and how this funding regularly turned drugs that failed to provide a meaningful clinical benefit in clinical trials into “safe and effective” medications that generated billions in revenues for the drug companies.

Part One

The Path to Open Payments

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began requiring drug companies to prove that their drugs were safe and effective in 1962, and for the next two decades, pharmaceutical companies regularly hired academic physicians to run their studies. As industry veterans later recalled, they often had to go with “hat in hand” to ask the academic physicians to do so. Grants from the National Institutes of Health were the coin of the realm for academic researchers at that time, not industry funding, and in order to get academic researchers to conduct their trials, pharmaceutical companies would have to cede control of the studies to them. The academic researchers would design the trials, analyze the results, and publish papers without interference from pharmaceutical companies.

This wall of separation began to thaw in 1980 once Congress passed the Bayh-Dole act, which allowed academic researchers who had made NIH-funded discoveries to license their discoveries to drug companies and collect royalties. The individual researchers could now profit from NIH-funded research, and thus academic researchers had a new reason to collaborate with industry. This impulse became more pronounced in subsequent years when it became more difficult for academic researchers to obtain NIH grants.

All of this occurred at the same time that the American Psychiatric Association (APA), with its publication of the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM III) in 1980, had adopted a disease model for categorizing mental disorders. The interests of psychiatry as a guild and those of the drug industry were now in perfect alignment.

With the APA’s new disease model, drug companies could get medications approved for a much broader range of difficulties. The market for psychiatric drugs was certain to dramatically expand. At the same time, psychiatry was now embracing psychopharmacology—as opposed to talk therapies—as its principal domain. Psychiatrists were now treating brain “illnesses,” with the prescribing of drugs their primary function. Both industry and psychiatry, acting in the manner of a guild, had reason to tout new drugs as safe, effective, and better than existing treatments on the market.

In the 1980s, the APA began allowing pharmaceutical companies to sponsor “educational” talks at its annual conference, with those talks given by academic psychiatrists who were being paid by the companies. The APA and pharmaceutical companies even publicly stated that they were now in a “partnership” to develop new drugs. Pharma money flowed to the APA for various purposes, and soon the drug companies were paying academic psychiatrists to serve as their advisors, consultants and speakers.

The pharmaceutical industry cast a wide net with its dollars, and this effort was so complete that in 2000, when the New England Journal of Medicine sought to find an expert to write a review article on the treatment of depression, it “found very few who did not have financial ties to drug companies.” As psychiatrist Daniel Carlat told the Boston Globe, “our field as a whole is progressively being purchased lock, stock, and barrel by the drug companies: this includes the diagnoses, the treatment guidelines, and the national meetings.”

During the next decade, it became evident that this “capture” of academic psychiatry by industry had come at great cost to the public. SSRI antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics had been pitched to the public in the 1990s as “breakthrough medications,” but it eventually became known, at least in certain circles, that clinical trial results of these two classes had been spun to exaggerate their efficacy, and drug harms had been hidden.

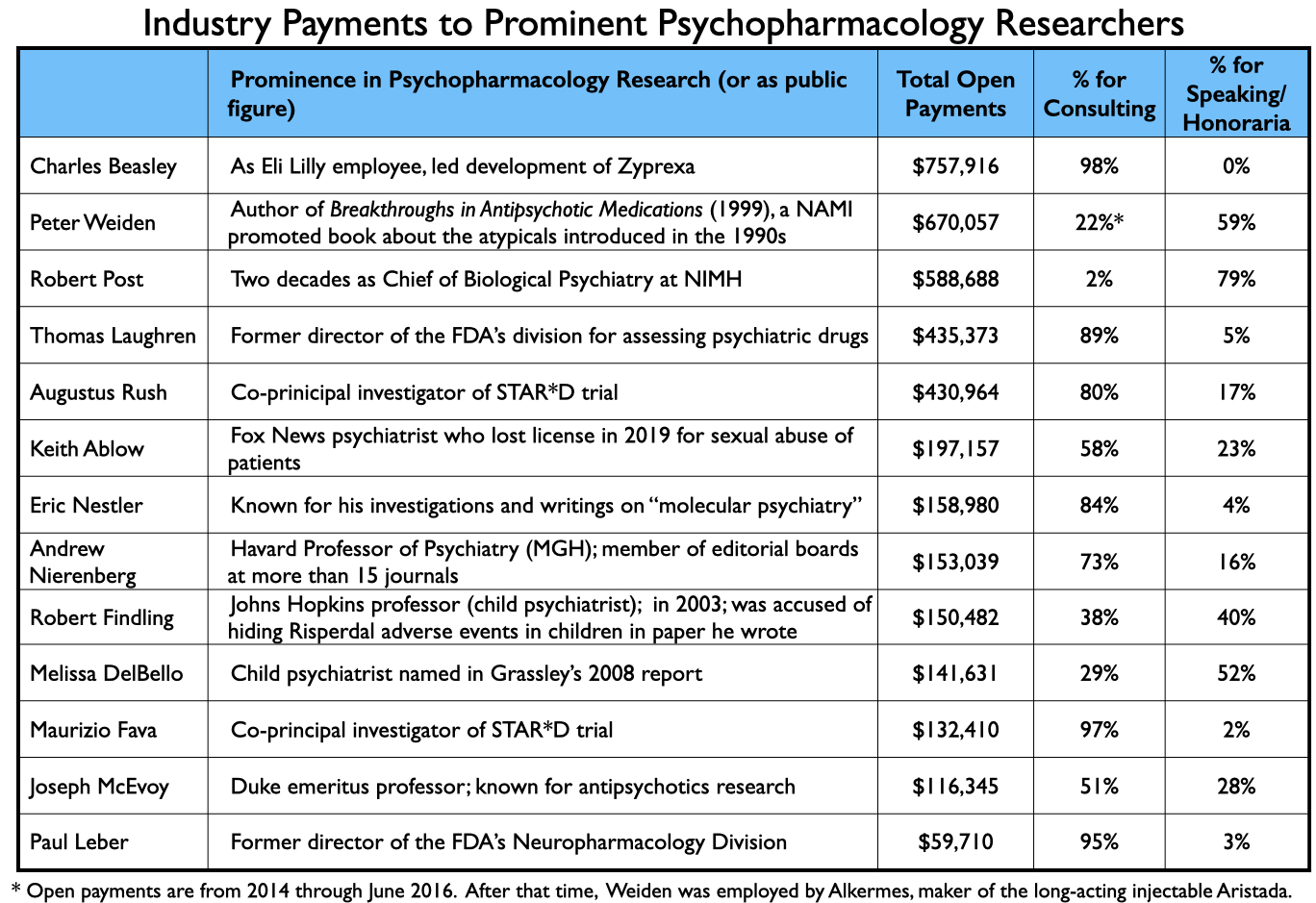

In 2007, Iowa Senator Charles Grassley began reporting the amount of industry money that was flowing to academic psychiatrists who had worked as consultants and served on speakers’ bureaus, and he named names. Grassley told of industry payments to Joseph Biederman, a professor at Harvard Medical School; to Melissa Del Bello, an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati; to Karen Wagner, director of child psychiatry at University of Texas; and to Charles Nemeroff, chair of the psychiatry department at Emory Medical School. Frederick Goodwin, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), was revealed as having been paid more than a million dollars to promote a mood-stabilizer for bipolar disorder.

In the wake of these revelations, Grassley pushed for legislation that would provide for the publication of industry payments to physicians. Starting in 2009, individual pharmaceutical companies began publishing these data on their websites, which were gathered by ProPublica into annual “Dollars for Doctors” reports. Then, in 2013, as part of the Obama Affordable Care Act, all pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers were required to report direct payments to physicians, with annual reports due by June 30 of the following year.

This “sunshine law” was expected to provide at least a partial remedy for the corruption that had become a public concern. Medical journals also began requiring authors of papers to disclose any financial conflicts of interest (but not the amount.) Such transparency would make the conflicts known, and, the thought was, this would produce a changed landscape for the testing of drugs in clinical trials. To protect their reputations, academic physicians would need to sever their financial ties to industry, and drug companies would be motivated to pay “independent” researchers to run their studies, as this would give more credibility to the published results.

The “sunshine” would help clean up the corruption.

Market Size

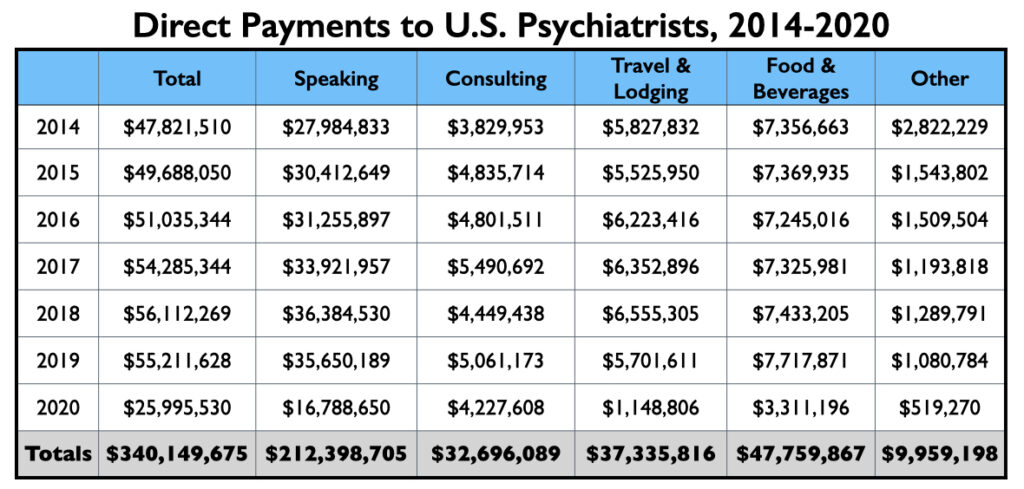

As the Open Payments database reveals, the Open Payments legislation has not achieved this end, at least within psychiatry. While the composition of the recipients of pharmaceutical money has changed, with salaried faculty at academic medical schools mostly disappearing from pharmaceutical payrolls, the flow of money to psychiatrists has continued. From 2014 to 2020, pharmaceutical companies paid $340 million to U.S. psychiatrists to serve as their consultants, advisers, and speakers, or to provide free food, beverages and lodging to those attending promotional events. Research support and payments for continuing education lectures are not included in this amount.

Of this total, $212 million was for speaking and $33 million for consulting purposes. The expenditures for travel, food and beverages tell of speaking events or conferences where drug companies are paying such expenses for the psychiatrists who attend or speak.

As can be seen in the graphic, yearly amounts of industry payments to U.S. psychiatrists ranged from $48 million to $56 million from 2014 through 2019. In 2020, with the Covid pandemic putting a halt to conferences and dinner events, industry payments dropped to $26 million.

In the pre-Covid years, 250 or so psychiatrists would each earn more than $50,000 for speaking/consulting services during the year, and another 500 or so would earn more than $10,000. This is the core number of psychiatrists earning a significant amount from industry annually.

Open Payments lists 31,784 psychiatrists who received something of value from the drug companies from 2014 through 2020, which is roughly 75% of the psychiatrists in the U.S. Most of those on this list received a free meal or beverage—these numbers tell of the reach that the industry has in terms of providing at least a favor or two to psychiatrists.

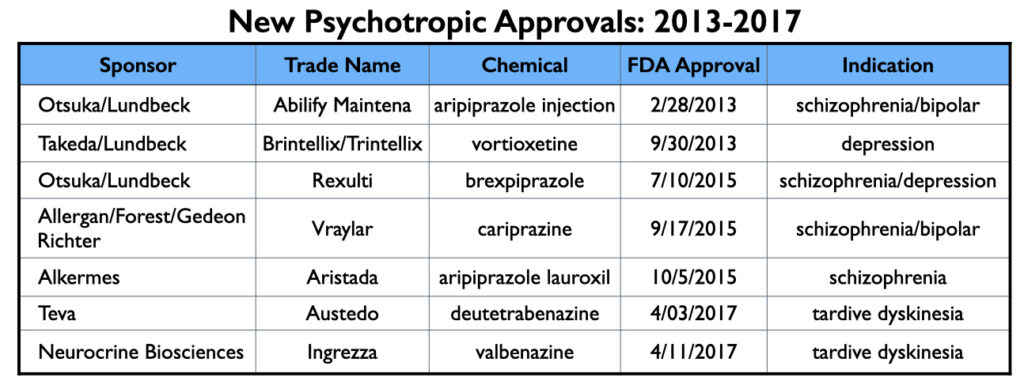

The FDA approved seven new psychotropic drugs from 2013 to 2017 (and thus were marketed during this 2014 to 2020 period), and as would be expected, the manufacturers of these seven drugs—Abilify Maintena, Brintellix/Trintellix , Rexulti, Vraylar, Aristada, Austedo and Ingrezza—provided the lion’s share of this promotional funding to U.S. psychiatrists during this time.

The Million-Dollar Club

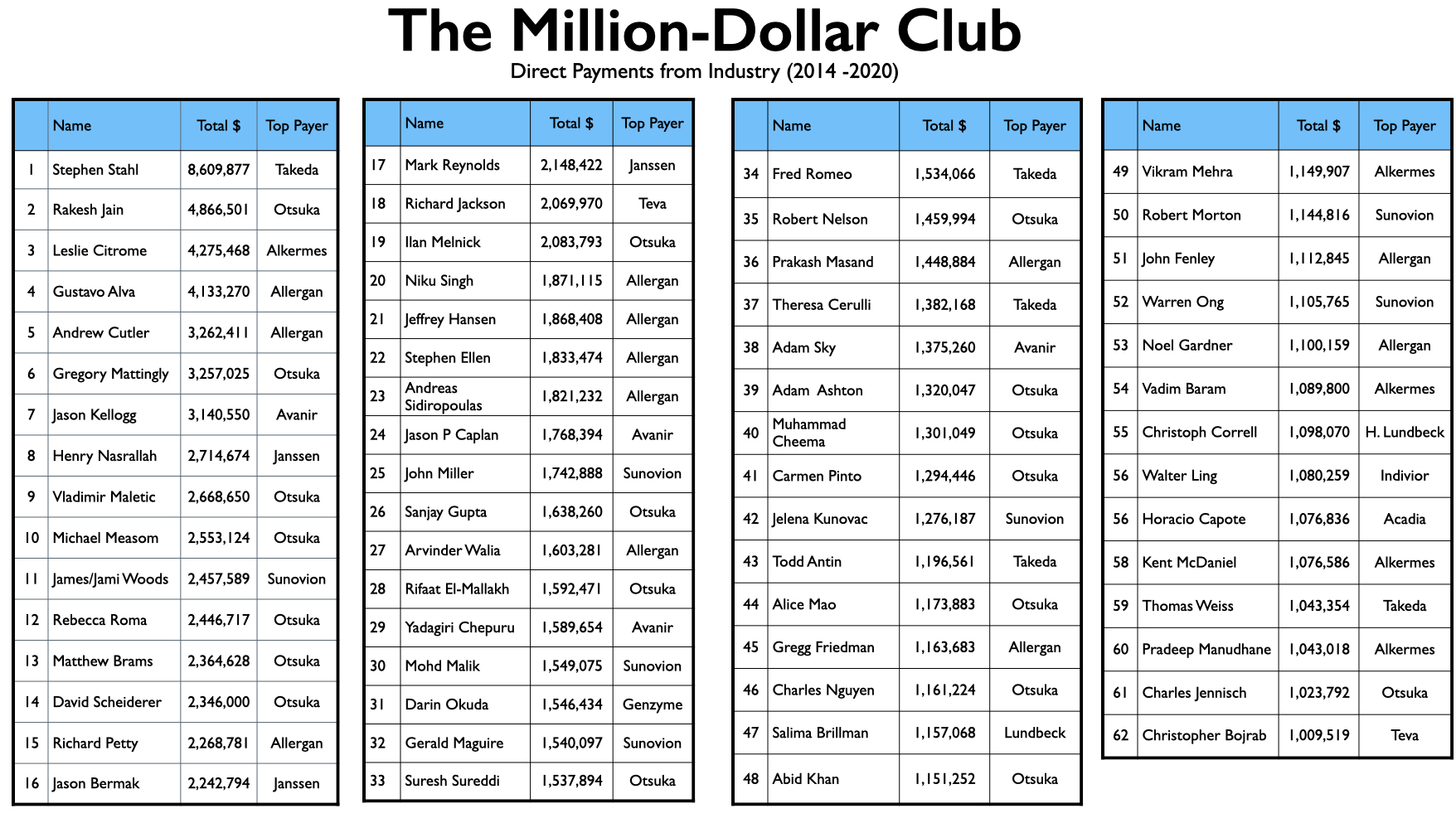

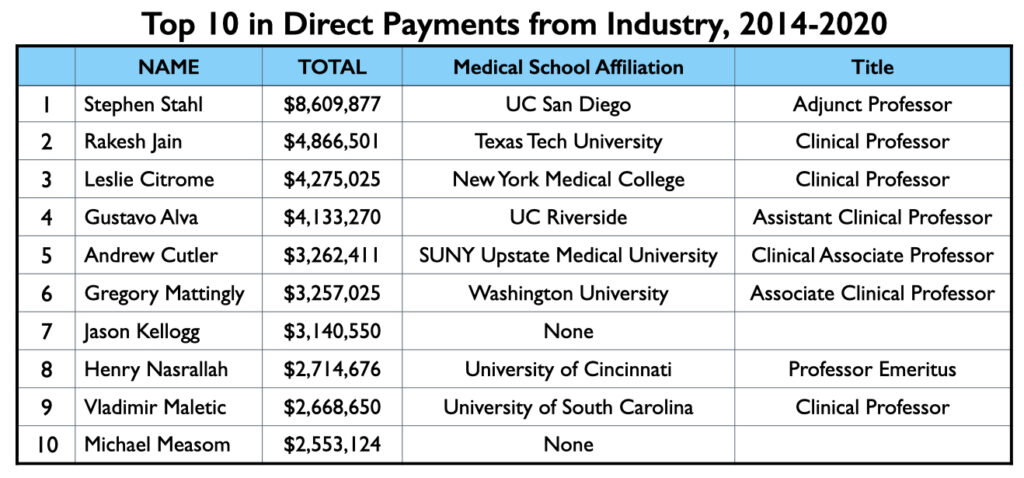

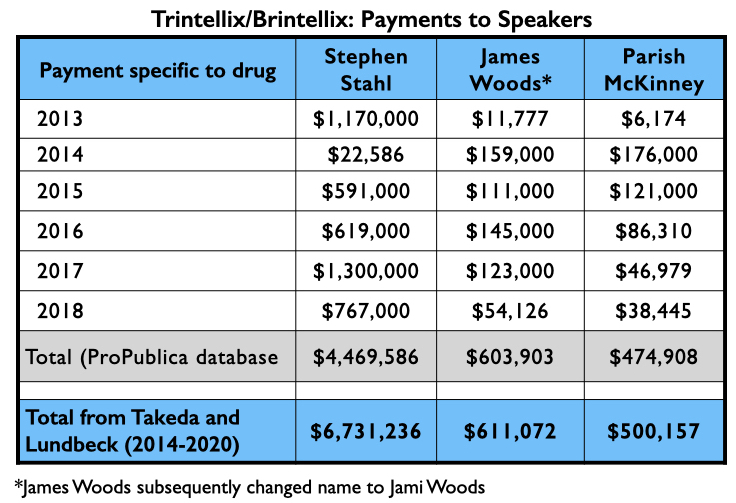

Mad in America (MIA) identified 62 U.S. psychiatrists who received direct payments from pharmaceutical companies totaling $1 million or more from 2014 through 2020. The top earner was Stephen Stahl, who earned $8.6 million, with $6.6 million coming from Takeda, which brought the antidepressant Brintellix to market in 2013. Takeda paid him $3.3 million for his promotion of this drug from 2014 through 2018.

To compile this million-dollar list, MIA searched through two online databases: ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs for 2018 (which is the latest year available on the site), and the Open Payments database from 2014 to 2020. While the Open Payments database cannot be used to generate a list of psychiatrists sorted from top to bottom by the total they received during this seven-year period, the ProPublica website can provide such a list for 2018. Thus, MIA first identified a list of 150 psychiatrists who earned more than $100,000 in 2018, and then checked the total that each one earned from 2014 to 2020, according to the Open Payments database.

That produced a list of 62 psychiatrists who made it into the million-dollar club. We also conducted a sampling of psychiatrists who were paid between $50,000 and $100,000 in 2018 for their services to pharmaceutical companies, but none hit the $1 million mark for the seven years. In addition, we used the Open Payments database to search through payments by the pharmaceutical companies that brought new drugs to market from 2013 to 2017 and identified the five or six psychiatrists that had been paid the most by each company. This didn’t turn up any new names for the list.

The list of 62 names is notable for the relative absence of academic psychiatrists known for their research. For the most part, the million-dollar club is composed of psychiatrists with clinical appointments to medical schools, which is often likened to serving as “adjunct” faculty, and who have private practices and work in the community. There are few salaried faculty at medical schools in this million-dollar club, and there are a fair number of psychiatrists on the list who have no connection whatsoever to an academic medical school.

This is true even of the top 10 on the list. There are no salaried faculty in this group. Seven of the ten have clinical appointments at medical schools, one is a professor emeritus, and two have no current affiliation with a medical school.

While the psychiatrists in the million-dollar club may not provide pharmaceutical companies with academic prestige, they do—as a group—provide industry with a range of helpful services, writing psychopharmacology texts, publishing reviews of new drugs in journals, serving on editorial boards of journals that publish reviews of new drugs, running continuing education companies, and so forth. And then there is the speakers’ circuit: a number of psychiatrists in the million-dollar club give more than 50 paid talks a year.

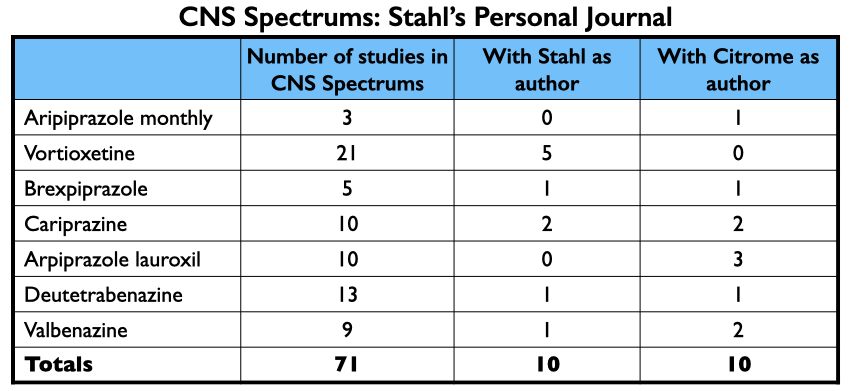

As noted above, Stephen Stahl sits at the head of this list, having been paid $8.6 million by pharmaceutical companies from 2014 through 2020, with 80% of that amount for “serving as faculty or as a speaker at a venue other than a continuing education program.” While Stahl may have only a clinical appointment at a medical school (UC San Diego), he is a star in the psychopharmacology world.

In 1991, Stahl’s career took a stumble when the Office of Scientific Integrity at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services determined that Stahl, then a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, had been the lead author on two papers that were “seriously misleading” and that he was guilty of plagiarism in a book chapter he had written. Stahl left Stanford for a position at UC San Diego and, in very short order, this mini-scandal was forgotten. For the past 25 years, he has arguably been the most influential psychiatrist in the world regarding the use of psychotropic medications, as his textbook, Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology, and his clinical manual, Essential Psychopharmacology Prescriber’s Guide, can regularly be found on the bookshelves of those who prescribe psychiatric drugs. In 2000, he founded the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI), a medical education company that produces webinars and continuing education courses on psychopharmacology. NEI also publishes CNS Spectrums, a peer-reviewed journal with Stahl as Editor-in-Chief. As new drugs are tested and earn FDA approval, he regularly writes articles about them, often focusing on their mechanism of action and publishing articles in his own journal. As his bio on the Neuroscience Education Institute website notes, he is a popular speaker on the lecture circuit:

“Lectures, courses and preceptorships based upon his textbooks have taken him to dozens of countries on 6 continents to speak to tens of thousands of physicians, mental health professionals and students at all levels. His lectures and scientific presentations have been distributed as more than a million CD-ROMs, internet educational programs, videotapes, audiotapes and programmed home study texts for continuing medical education to hundreds of thousands of professionals in many different languages. His courses and award-winning multimedia teaching materials are used by psychopharmacology teachers and students throughout the world. Dr. Stahl also writes didactic features for mental health professionals in numerous journals.”

NEI openly promises pharmaceutical companies that it can help them sell their drugs. Its 2021 Congress, which is scheduled for November, features presentations by a number of the industry’s favorite speakers, and drug companies are urged to pay for exhibits that will help them “connect with 2000+ U.S.-based mental health professionals, 95% of whom have prescribing privileges.” Pharmaceutical companies may also pay to “host” symposiums to “educate a dedicated audience of prescribers.” Together, the exhibits and symposiums provide drug companies with an opportunity to “increase brand recognition and drive attendee interest to your product.”

Rakesh Jain, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Texas Tech University School of Medicine, occupies the second spot on the million-dollar list. His 41-page resume features a long list of activities of use to pharmaceutical companies: principal investigator on clinical trials (and occasionally a contributing author to research results); advisor to more than 15 pharmaceutical companies over the years; regular presenter on the CME circuit; reviewer for more than a dozen medical journals (most with a focus on drug therapies); numerous media appearances; and speaker for dozens of companies. Pharmaceutical companies paid him $4.867 million from 2014 to 2020, with 67% of this amount for speaking services, 19% for “honoraria” and travel expenses, and 14% for consulting. He provided services to more than 30 pharmaceutical companies during this period.

Number three on the million-dollar list is Leslie Citrome, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at New York Medical College in Valhalla, New York. While not quite the star that Stahl is in the psychopharmacology world, he is a person of great influence. He is currently president of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology. The society’s “official journal” is the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, a favorite venue for pharmaceutical companies as they publish clinical trial results. The society is also a provider of continuing medical education courses. Citrome consults with drug companies as they test and market their new drugs, and once a drug is approved, he regular writes reviews that expand, in one way or another, on the evidence for their safety and efficacy. He serves on the board of 11 medical journals, and as his Linkedin profile states, he has “lectured extensively throughout the USA, Canada, Europe, and Asia.”

Pharmaceutical companies paid Citrome $4.275 million for his services from 2014 to 2020, with 55% of this total for lectures and talks, and another 25% for consulting services. The remaining 20% was for honoraria, grants, gifts, and travel expenses. Twelve pharmaceutical companies paid him more than $100,000 during this seven-year period.

Another route to getting on industry’s speed-dial for speaking services is to serve as a principal investigator in clinical trials, or, even better, running a for-profit company that conducts industry-funded clinical trials. Jelena Kunovac is one of several with this experience on her resume. In 2012, she founded Altea Research in Las Vegas, and as its website states, Altea “partners with major pharmaceutical sponsors to conduct clinical research trials for new medications and treatments primarily in the area of psychiatry.” Since 2014, she has been paid $1.276 million for her regular presence on the speaker’s circuit. Most of this work came from three companies: Sunovion (Latuda); Alkermes (Aristada); and Otsuka (Rexulti and Abilify Maintena.)

Prakash Masand, 35th on the list, has long prospered as a provider of continuing medical education services. An adjunct professor at the Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, he founded psychCME. After that company was acquired by United Health Group in 2006, he founded a second CME company, Global Medical Education, which was acquired by Clinical Care Options in 2020. Pharmaceutical companies provide support to CME companies, which is used to pay speakers at CME events, but since the companies “independently” select the speakers, these payments don’t show up in the Open Payments database. Such events, of course, are another way that drug companies create a market for their new drugs and ultimately funnel money to speakers, and this has made Masand, as an owner of CME companies, of considerable value to the industry.

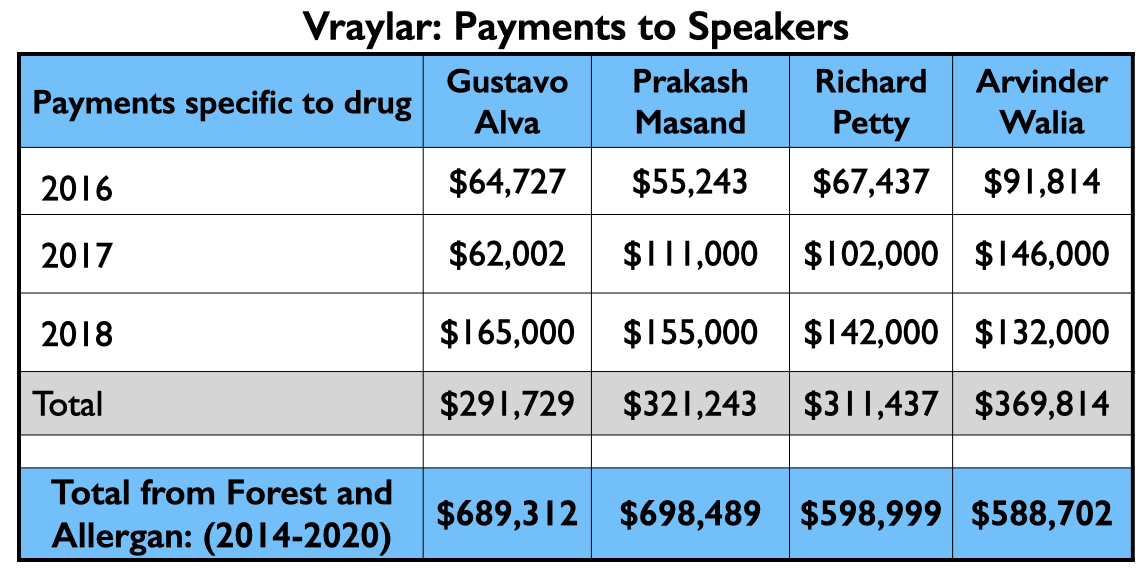

On a personal level, Masand was paid $1.448 million from 2014 through 2020, with 84% of this funding for speaking and related travel expenses. Much of this pay came from Allergan for promoting Vraylar, an antipsychotic.

Others on the list have built careers as speakers without any academic affiliation. For instance, Rebecca Roma, a psychiatrist in the Pittsburgh area, earned $2.446 million from 2014 through 2020, with 90% for speaking and related travel expenses. Otsuka, Janssen, and Alkermes were her three top clients. In a similar vein, Christopher Bojrab, who is the team psychiatrist for the Indiana Pacers, earned $1 million during the seven years, serving as a speaker for a half-dozen or so companies. His bio tells of how he gives more than 100 lectures each year.

Once psychiatrists move into the top tier of speakers, they can expect to remain there, particularly if they develop ties to multiple companies. Most of those in the million-dollar club generate steady six-figure incomes year after year (although such payments dropped notably in 2020 during the pandemic, as in-person conferences and events disappeared).

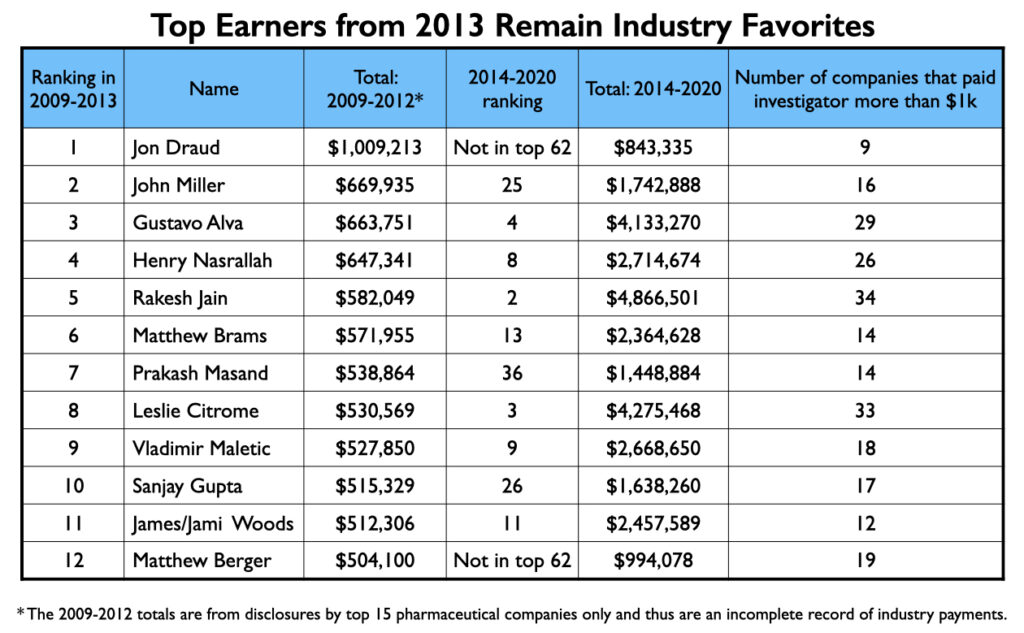

In 2013, ProPublica published an article detailing how 22 physicians, based on disclosures from the 15 largest pharmaceutical companies, had earned more than $500,000 from 2009 to 2012 for their speaking and consulting activities. Twelve of the 22 were psychiatrists, and all 12 show up prominently in the Open Payments database. Five of the 12 are among the top 10 in psychiatry’s million-dollar list, and five others are in the club. The remaining two just missed hitting this mark.

The most prominent academic psychiatrist who shows up in the million-dollar club is Christoph Correll. A professor of psychiatry at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, he is well known for his research on antipsychotics. Another prominent academic on the list is Rifaat El-Mallakh, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Louisville School of Medicine known for his expertise in mood disorders. His appearance on the list is somewhat surprising given that he has authored several articles on how antidepressants can cause tardive dysphoria and, even more broadly, on how psychiatric drugs may induce an “oppositional tolerance” that leads to long-term “treatment resistance” and chronic illness.

The most prominent academic psychiatrist who shows up in the million-dollar club is Christoph Correll. A professor of psychiatry at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, he is well known for his research on antipsychotics. Another prominent academic on the list is Rifaat El-Mallakh, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Louisville School of Medicine known for his expertise in mood disorders. His appearance on the list is somewhat surprising given that he has authored several articles on how antidepressants can cause tardive dysphoria and, even more broadly, on how psychiatric drugs may induce an “oppositional tolerance” that leads to long-term “treatment resistance” and chronic illness.

The payments to academic psychiatrists who served as authors of papers relating to the seven new drugs are discussed in Part Two. Here is a sampling of payments to other prominent psychiatrists that provided consulting or speaking services to industry from 2014 through 2020:

The Façade Is Gone

From a public health perspective, the clinical testing of new drugs is supposed to provide evidence that a drug is safe and effective, and thus can provide a medical “benefit” to society. The published results of these trials then serve as findings that are promoted to prescribers through textbooks, CME courses and conferences that “inform” the medical community about what science has revealed about a new medication.

For the public to trust that science, it needs to believe that it is free from commercial influence. The trials should be conducted by independent investigators, and subsequent reviews of the drug and conference talks should be free of industry taint as well. More than a decade ago, the public became disenchanted when it learned that beneath a façade of scientific integrity, with reports of clinical-trial results listing academic psychiatrists as authors, the pharmaceutical companies were now designing the trials, analyzing the results, and ghostwriting papers. The named authors were lending their academic prestige to this process, as though they were still the ones controlling the research.

That façade is now gone. In this era of disclosure, the companies’ control of the research, and the lack of any independent testing of the drugs, are now quite visible.

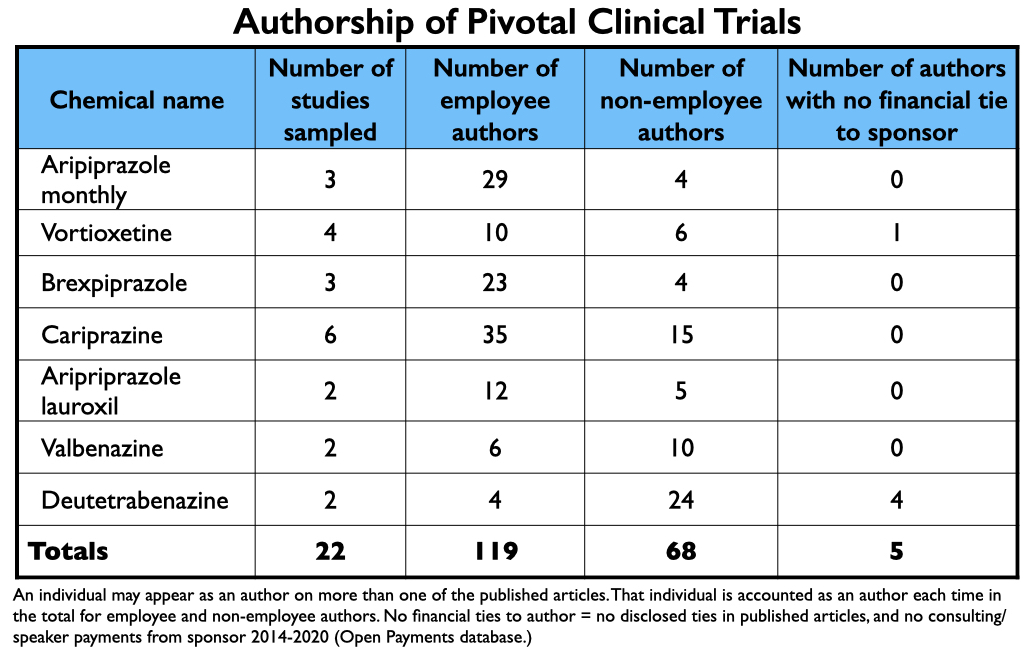

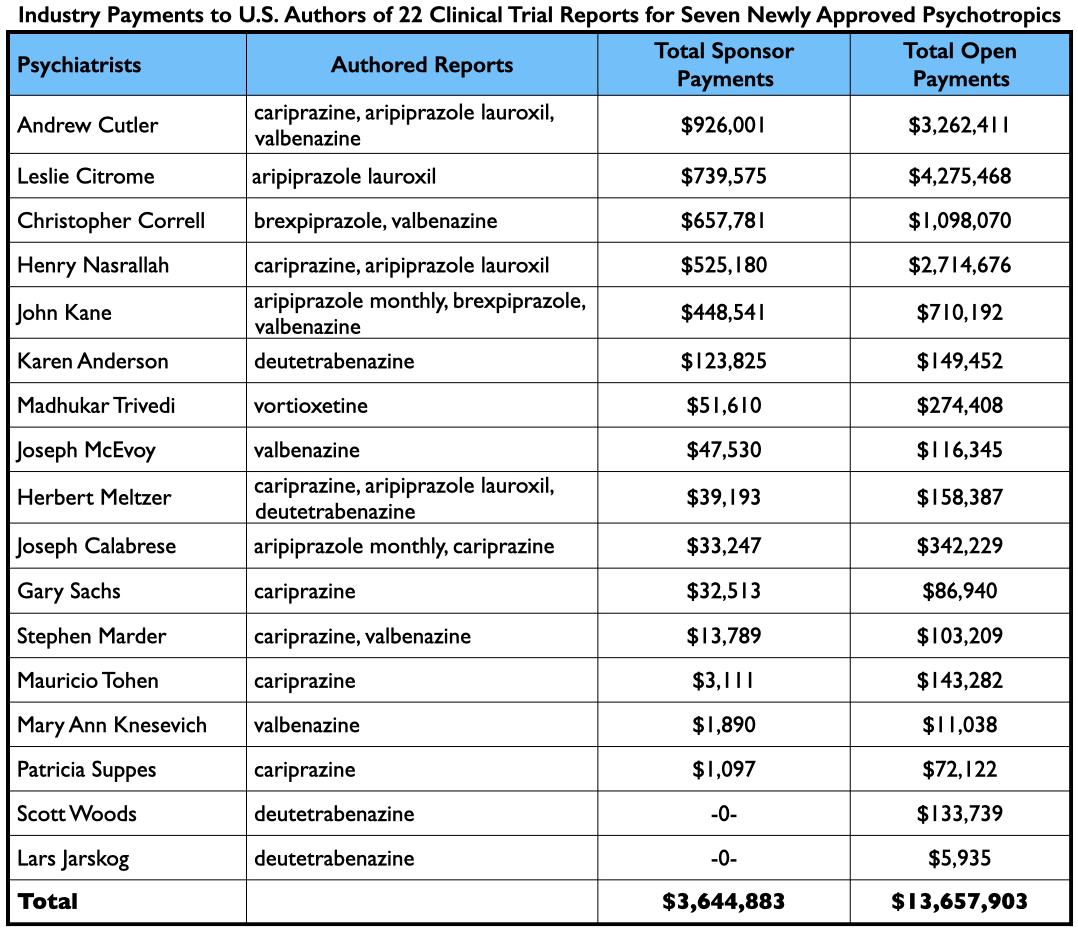

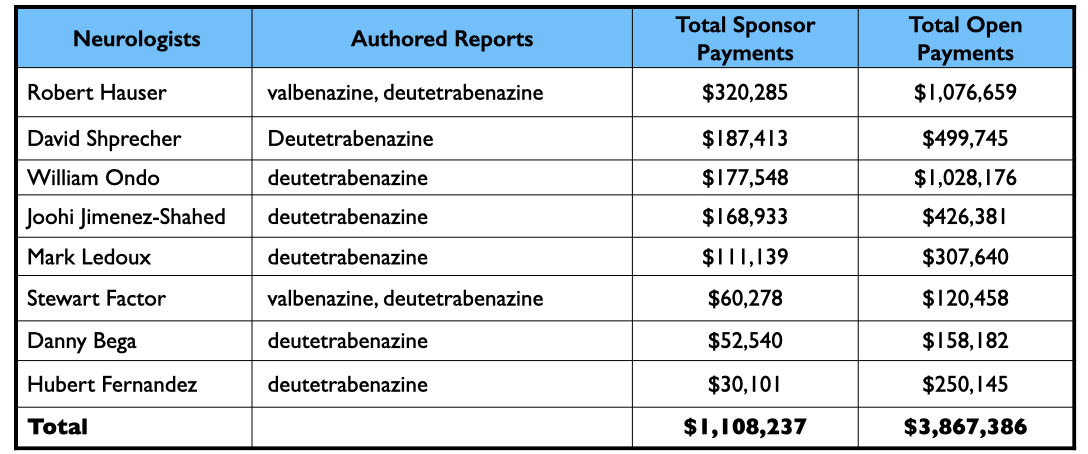

From 2013 through 2017, the FDA approved two long-acting formulations of aripiprazole, two antipsychotics (tested for multiple indications), an antidepressant, and two drugs for tardive dyskinesia. MIA sampled 22 published reports of their clinical trial results, and while this sample isn’t exhaustive of all such reports, it is representative.

Every article listed at least two company employees as authors. While usually a non-employee was listed as the lead author, four articles on cariprazine listed an employee as a lead author. Most remarkable, two owners of the patent for cariprazine were listed as authors on five of the articles reviewed by MIA.

In total, there were 187 named authors on the 22 reports. One hundred nineteen were employees. As for the 68 non-employees named as authors, there were only five instances where an author didn’t have a financial tie to the sponsor, either during the study (as disclosed in the published report), or at some point from 2014-2020 (as disclosed in the Open Payments database).

As there were a number of authors named on two or more reports, the number of individuals authoring reports was much less than 187.

Many of the trials were conducted abroad, and given that the majority of authors were company employees, there were a surprisingly small number of U.S. psychiatrists on the roster of authors. Seventeen U.S. psychiatrists and eight U.S. neurologists were named as authors in the 22 reports (who were listed a total of 49 times.) Twenty-three of the 25 received payments from the pharmaceutical companies that sponsored the trials, either during the trial or after FDA approval of the drugs.

Many of the trials were conducted abroad, and given that the majority of authors were company employees, there were a surprisingly small number of U.S. psychiatrists on the roster of authors. Seventeen U.S. psychiatrists and eight U.S. neurologists were named as authors in the 22 reports (who were listed a total of 49 times.) Twenty-three of the 25 received payments from the pharmaceutical companies that sponsored the trials, either during the trial or after FDA approval of the drugs.

As a group, the 25 U.S. physicians were paid $4.8 million for their consulting/speaker services to pharmaceutical companies whose drug they had “tested.” However, many of the 25 provided consulting and/or speaker services to a multitude of other pharmaceutical companies, evidence of how they were a go-to group for industry, with collective earnings of $17.5 million from 2014-2020.

A Pretense of Science

The fact that the façade of an independent evaluation is now gone might be seen as an improvement: The commercial aspect is out in the open. However, the pretense that the trials are a scientific enterprise remains. And while this may seem counterintuitive, disclosure requirements help create this pretense.

In the published reports, the companies list their employees as authors and the non-employees disclose their financial ties to the sponsor and to other pharmaceutical companies. The disclosure lists of the non-employees may go on and on, and often appear in small print that is difficult to read. But this “transparency” is presented as evidence of compliance with sunshine laws, and thus part of an accepted scientific process. The published reports then tell of “statistically significant” results from “double-blind, placebo-controlled trials,” which is language informing readers that such results emerged from a methodologically proper assessment of the drug.

Together, the disclosures and the scientific language in the published reports help obscure the obvious, which is that the testing of psychiatric drugs—and the reporting of the results—occur completely within a commercial context. The drug companies want to see their experimental drugs declared “safe and effective,” and they hire consultants with the expectation that they will help them achieve this end. The influence of money all flows toward achieving that goal.

Moreover, the payment to those who author trial results is simply the first step in a drug-development process that is greased by pharmaceutical money from beginning to end.

The Psychopharmacology Journals

Few clinical trial results involving psychiatric drugs are published in prestigious medical journals. Instead, they are published mostly in journals with a focus on “psychopharmacology.” Such articles regularly tell of drugs that are “safe and effective,” with discussions on how the new drugs may provide a therapeutic benefit of some sort over existing drugs on the market.

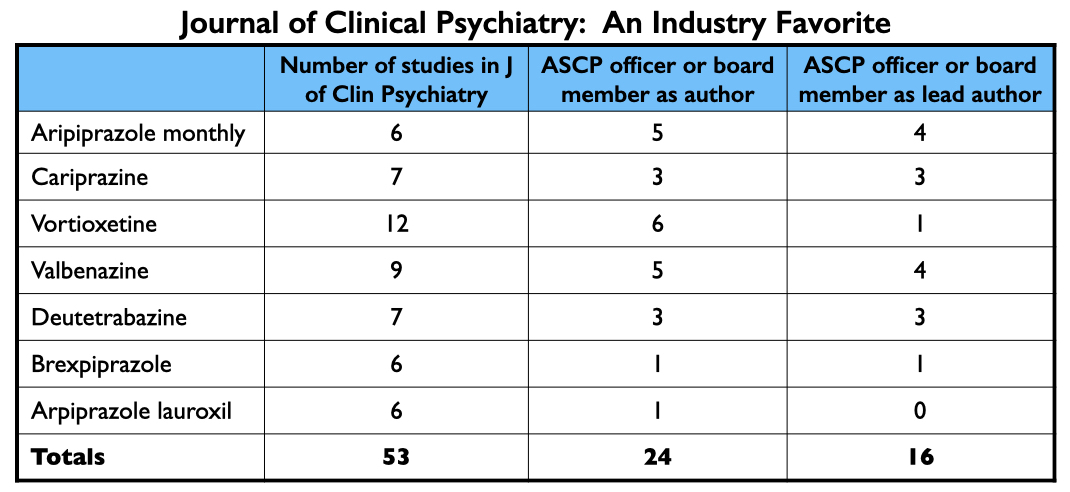

One common landing spot for such reports is the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. While it may not be a prestigious journal, it has a big impact: the journal states that it is the most widely cited “clinical psychiatry journal” in the world, with nearly 22,000 citations annually. As noted above, it is the official journal of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP).

Seven of the 22 reports described above were published in this journal. Moreover, once initial trial results are published, then other “experts” in psychopharmacology, such as Leslie Citrome and Stephen Stahl, publish review articles that describe the drugs’ mechanism of action, findings from the clinical trials, and how the new drugs compare to similar drugs already on the market. Often, these review articles will suggest that the new drug has slightly greater efficacy or fewer side effects, a bottom-line nugget that can prompt prescribers to try the drug. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry serves as home for these articles too.

In total, the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry published at least 53 articles about the seven drugs approved from 2013 to 2017. Twenty-four had an ASCP officer or board member listed as an author; an ASCP board member was the lead author on 16 of the 53. Nearly every officer and board member of the ASCP has financial ties to industry.

In total, the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry published at least 53 articles about the seven drugs approved from 2013 to 2017. Twenty-four had an ASCP officer or board member listed as an author; an ASCP board member was the lead author on 16 of the 53. Nearly every officer and board member of the ASCP has financial ties to industry.

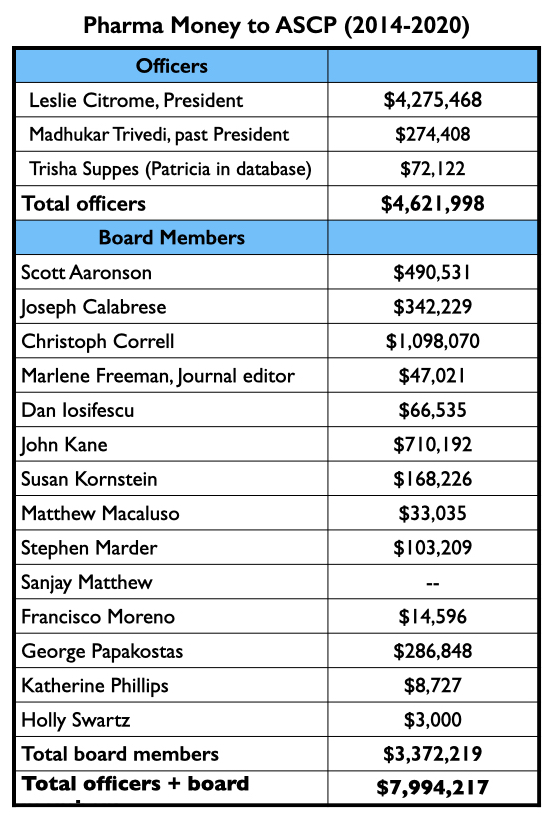

The three ASCP officers, led by Leslie Citrome, were collectively paid $4.62 million by drug companies to serve as consultants or speakers from 2014 through 2020. The 14 ACSP board members were paid $3.37 million for these purposes during this time.

In sum, during the period that the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry published at least 53 reports about the seven new drugs, ASCP officers and board members were paid $8 million by pharmaceutical companies, with most of this funding coming from the makers of the new drugs.

CNS Spectrums is another industry-friendly journal. As noted above, Stephen Stahl is its editor-in-chief, and the journal is published by the medical education company he founded, Neuroscience Education Institute. CNS Spectrums published at least 71 articles about the seven new drugs, with Stahl and Citrome each authoring 10 of them.

Together, Stahl and Citrome were paid $12.9 million by pharmaceutical companies from 2014 to 2020. Most of this funding was for giving talks: $6.9 million for Stahl; $2.4 million for Citrome.

Together, Stahl and Citrome were paid $12.9 million by pharmaceutical companies from 2014 to 2020. Most of this funding was for giving talks: $6.9 million for Stahl; $2.4 million for Citrome.

The CME Money Tree

The Open Payments database provides a record of $340 million in direct payments from pharmaceutical companies to U.S. psychiatrists from 2014 through 2020. In addition, pharmaceutical companies provide funding to continuing medical education companies to hold courses and events. This funding, while it flows to speakers, isn’t included in the Open Payments database because the CME company, not the drug company, selects the speakers. Thus, it isn’t a direct payment to the speakers, but these speakers are often the same psychiatrists that are being paid by the drug company to serve as their consultants and speakers. Critics of this non-disclosure practice have likened it to “money laundering.”

From 2014 through 2020, industry payments to CME companies totaled $5.1 billion. A rough estimate, based on available data, is that this would have provided an additional $100 million in speaking fees to U.S. psychiatrists during this period.

Such is the “big picture” of the psychopharmacology industry. The influence of all money flows in one direction, and at every step—the design of the clinical trials, the publication of the results, and the subsequent publicizing of those results—the money is spent toward telling a story that will result in commercial success. There is not a single dime spent for serving the public good, which would be a process designed to critically assess the overall effects of a drug and to communicate those findings, even if negative, to the medical community and to the public.

Part Two

Case Studies of Seven New Drugs

If industry funding of psychiatrists didn’t compromise the testing of investigational drugs and the subsequent dissemination of results, then perhaps it could be seen as a commercial process that nevertheless rested on decent science. The seven new psychiatric drugs approved from 2013 through 2017 provide case studies for assessing whether that is so.

Here are some common elements to look at when critiquing the merits of clinical trial reports on psychiatric drugs:

- Do inclusion criteria, or the design of the protocol, select for a subgroup of patients that could be expected to be good responders to the study drug?

- Do inclusion/exclusion criteria select for a subgroup of patients that could be expected to do poorly when switched to placebo?

- Is there a true placebo group in the study, or is the placebo group composed of chronic patients who have been withdrawn from the psychiatric medications they had been on?

- Have multiple doses of the study drug been compared with a single dose of placebo, which gives the study drug “multiple” chances to turn up a statistically significant benefit?

- Is the statistically significant “efficacy” finding, which tells of a point difference in reduction of symptoms between the drug treatment and placebo, of clinical significance? Researchers call this standard the “minimum clinically important difference,” and it regularly requires a greater point difference than statistical significance does.

- Is the conclusion in the abstract consistent with the data presented in the paper?

The composition of the placebo group, of course, is of particular importance. If it is a drug-withdrawn group, these patients may experience a variety of psychiatric and physical difficulties that worsen their outcomes on efficacy measures and lead to a much higher incidence of adverse effects than would be the case in the normal course of the “illness.”

These are all questions that can be investigated by “deconstructing” the published reports. If these machinations exist, they should be visible in the papers. What remains unknown from such a review is whether a drug company and its authors have spun the presentation of the data or hidden adverse events, and how many failed trials were never published. What follows, with one exception, is a look at published papers that tell of positive results for the drugs.

Abilify Maintena (injectable aripiprazole)

Otsuka and Lundbeck brought Abilify Maintena, a long-acting formulation of aripiprazole, to market in 2013 as a treatment for schizophrenia and in 2017 as a maintenance treatment for bipolar 1.

In reports of three pivotal studies for these two conditions, 18 of the 21 authors were company employees. Two of the three non-employees were U.S. psychiatrists, John Kane and Joseph Calabrese. Kane was the lead author on two schizophrenia studies, while Calabrese was the lead author on a bipolar study. Both are board members of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology.

The published results

In the maintenance trial for schizophrenia, the researchers enrolled 843 schizophrenia patients who had a “history of symptom exacerbation or relapse when not receiving antipsychotic treatment.” All enrollees were then “cross-titrated” from the antipsychotic they had been on to oral aripiprazole. Those who stabilized on this drug for four weeks were transitioned to injectable aripiprazole once monthly, and those who stabilized well on the injectable for three months were randomized into a double-blind trial, with one group maintained on the injectable and the other given a placebo injection.

With this design, 403 of the initial 843 enrollees made it to randomization. Only 10% of the drug-maintained group relapsed during the weeks and months that followed, versus 40% of the placebo group. “The new IM-depot formulation of aripiprazole is effective for preventing relapse in schizophrenia and represents an alternative treatment option with a safety profile similar to oral aripiprazole,” concluded Kane and the company employees who authored the report. The article, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, was titled “Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.”

The maintenance study in bipolar 1 patients had a similar design. Patients who were experiencing a manic episode were first stabilized on oral aripiprazole and then on the injectable for several months. This select group of good responders to Abilify Maintena were then randomized to continued treatment with the injectable or placebo. Twenty-seven percent of the medicated patients experienced a mood episode during the 52-week follow-up compared with 51% of the placebo group. “These findings,” wrote Joseph Calabrese and the company employees, “support the use of aripiprazole once monthly (AOM 400) for maintenance treatment of BP-1.”

The critique

The bias-by-design in these studies is evident. In the schizophrenia study, the inclusion criteria selected for patients who had a history of doing poorly when stopping antipsychotic medication, which helped select for patients who could be expected to worsen when randomized to placebo. Then the protocol, through its extensive stabilization phase, selected for a group of good responders to Abilify Maintena (403 of 843 initial enrollees). At randomization, this select group had a mean score of 54.5 on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS), meaning they were only “mildly ill.” Given the design of this study, those randomized to continued treatment with Abilify Maintena could expect to remain stable, which is what occurred. Their PANSS scores stayed the same. However, those switched to placebo began to worsen within two weeks, with their PANSS scores rising fairly quickly into the mid-60s, at which point many were classified as nearing “relapse” and discontinued from the study. Sixty-two percent in the placebo group suffered “treatment emergent” adverse events, such as akathisia, anxiety, headache, and tremors, all of which are known withdrawal symptoms.

Yet, even given this biased design, the 12-point difference in mean PANSS scores between the two groups at the study’s end, 66 to 54, did not rise to the level of providing a clinically significant benefit. PANSS is a 210-point scale, and researchers have determined that there needs to be at least a 15-point difference between drug and placebo for the treatment “benefit” to be of clinical importance.

Moreover, starting from the moment of initial enrollment, only a small minority of patients stabilized on Abilify Maintena and remained stable during the double-blind trial. Although the math is a bit complicated, the failure rate for patients treated with Abilify Maintena—either in the stabilization phase or after being randomized to the drug arm of the trial—was 72%. The researchers also stopped the trial early, such that there were only 23 patients in the study who had remained stable on Abilify Maintena for 52 weeks, a documented long-term “stabilization” rate of 3%. Yet, the title of the published article told of how this treatment had proven to be an effective “maintenance treatment” for a full year.

As for adverse events, two patients in the Abilify Maintena arm died, including one from a coronary event, but the investigators concluded that these deaths were “unrelated” to the treatment.

The numbers are only slightly better for the bipolar trial. There were 731 patients enrolled into the study, and of this group, 266 stabilized well enough on Abilify Maintena to be randomized into the trial. Of the 133 randomized to the drug arm, only 64 stayed well and in the trial to its end (52 weeks). There were 598 patients who had the chance to stabilize on the drug and be maintained on it following randomization (731 minus 133 randomized to placebo); the documented stabilization rate at one year for this consistently medicated group was 11% (64/598).

The money tree

Kane published a second study finding that Abilify Maintena was a safe and effective treatment for acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. Once the results from the pivotal trials were published, others then published reviews of the Abilify Maintena data, helping to make a case for its use. Leslie Citrome wrote three articles discussing Abilify Maintena, one of which told of how he had developed a “hypothetical model” for comparing it to Invega, a long-acting injectable already on the market, and in this comparison, Abilify Maintena produced better clinical outcomes and reduced rehospitalization rates, which would produce substantial cost-savings for society even though Abilify Maintena’s prescription cost was much higher than Invega’s.

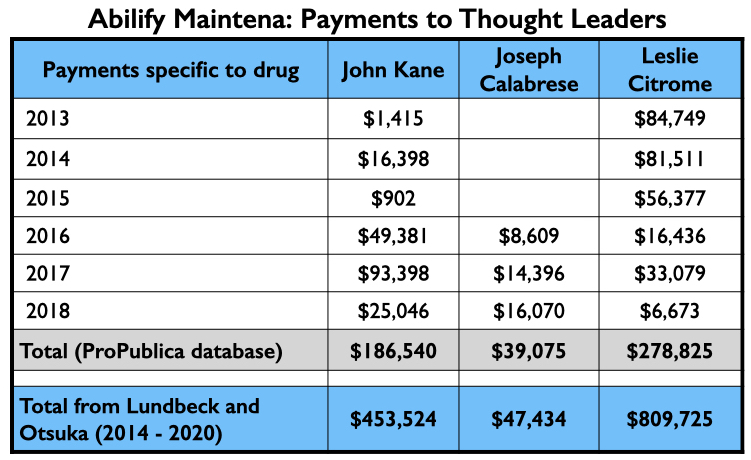

Here is the industry money that flowed to Kane, Calabrese and Citrome for their consulting and or speaker services specifically related to Abilify Maintena from 2013 through 2018 (ProPublica database), and their total payments from Lundbeck and Otsuka—the two marketers of Abilify Maintena—from 2014 through 2020 (Open Payments database).

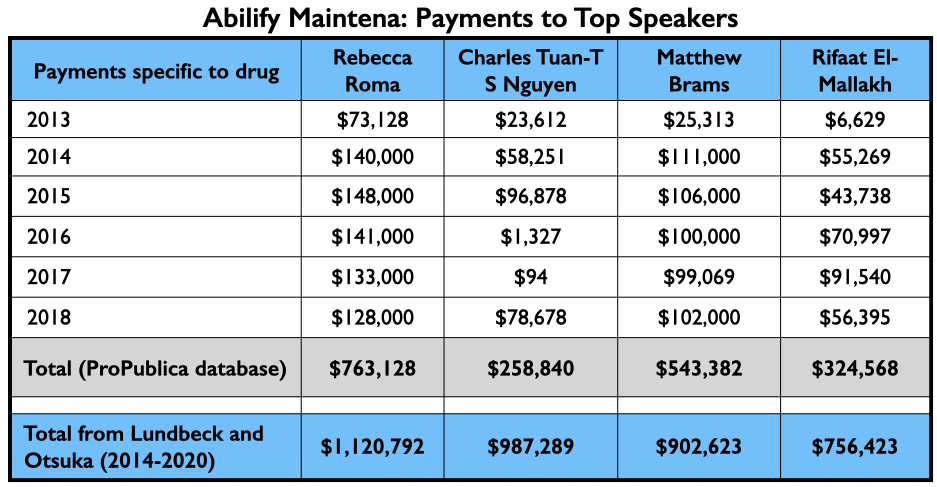

Once Abilify Maintena was approved, Otsuka and Lundbeck sent their speakers out into the world. Two of their four top-paid speakers, Rebecca Roma and Charles Tuan-S Nguyen, appeared regularly on Psych U, which is how Otsuka and Lundbeck branded their online “educational services.” The third, Matthew Brams, helped pitch Abilify Maintena to committees that approve Medicaid payments for drugs. The fourth, Rifaat El-Mallakh, provided Otsuka and Lundbeck with a speaker that could lend academic prestige to their promotional efforts.

Here is the money they earned for promoting Abilify Maintena from 2013 through 2018 (Pro Publica database), and the total they earned from Lundbeck and Otsuka from 2014 through 2020. (Open Payments database.)

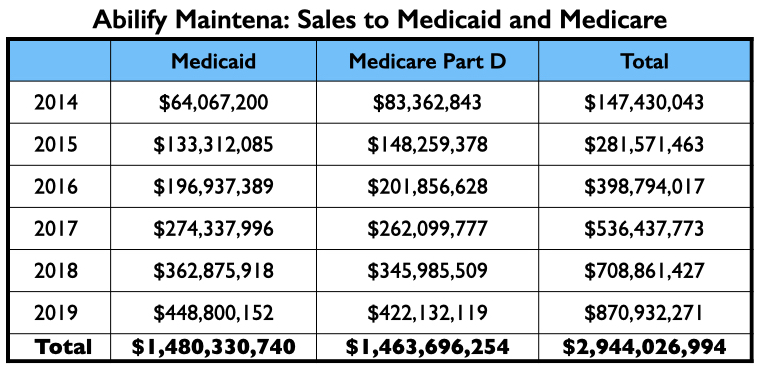

This three-step process—publication of the trial results, further reviews of the trial results, and then the promotion of the drug through dinner talks, conferences, and online presentations—turned Abilify Maintena into a commercial success, with sales to Medicare and Medicaid alone totaling $3 billion from 2014 through 2019. Sales to private health insurers and non-U.S. sales are not included in this total.

Trintellix/vortioxetine

Trintellix/vortioxetine

Takeda and Lundbeck obtained FDA approval for vortioxetine as a treatment for depression in 2013, marketing it as Brintellix. In 2016, they changed the trade name to Trintellix.

In four reports of pivotal clinical trials, eight of the authors were employees of Takeda or Lundbeck. Of the five non-employee authors, four disclosed they had been paid by at least one of the sponsors for consulting and/or speaker services. The only U.S. psychiatrist named as an author in the four reports was Madhukar Trivedi, who was a consultant to both sponsors.

The published results

Three trials assessed various doses of the drug versus placebo for up to eight weeks. Together, the trials told of five comparisons with placebo that were positive for vortioxetine (at 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg and 20 mg.), and one comparison where it did not show efficacy (at 10 mg). A fourth study found that the drug was effective at reducing the risk of relapse.

Five well-known U.S. psychiatrists, led by Alan Schatzberg, along with a Canadian psychiatrist, subsequently published an “overview of vortioxetine” in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. They wrote the following:

- That this “novel antidepressant” was understood to “enhance levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, acetylcholine and histamine in specific areas of the brain,” which, at least in theory, could provide “potentially unique, beneficial outcomes in patients treated with the agent.”

- That it had proven to be effective in treating depression “in six clinical trials.”

- That its “multimodal pharmacologic activity may convey benefit in cognitive function.”

- That its “favorable tolerability profile may have meaningful advantages with regard to weight gain and low sexual dysfunction that may benefit patients.”

Leslie Citrome published several reviews related to vortioxetine and concluded that in comparison with other antidepressants already on the market, it was equally efficacious but possibly more tolerable and with fewer side effects.

The critique

At first glance, the three short-term trials do tell of an effective drug. Even though multiple doses of vortioxetine were compared with one dose of placebo in the trials, vortioxetine produced a statistically significant benefit in five of the six comparisons, and the difference in those five comparisons ranged from 3.6 points to 7.1 points on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), a drug-placebo separation understood to provide a clinically important benefit.

There is the usual problem that the placebo group in each of these studies was composed of drug-withdrawn patients. There was also a design feature in the studies conducted outside the United States—and possibly in the U.S. trials too—that tells of a deliberate effort to downplay adverse events with vortioxetine. Rather than have investigators question patients about specific side effects known to be associated with antidepressants (such as sexual dysfunction), the protocol told investigators to simply ask patients “How do you feel?” Having patients self-report their adverse reactions can be expected to produce a much-reduced tally of adverse events, which, in this case, led to a conclusion that this drug was less likely to cause sexual dysfunction than other antidepressants already on the market.

But the efficacy in the published trials remains. However, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, in a subsequent review of the data submitted to the FDA, found that there had been 10 trials of vortioxetine, rather than the six cited by Schatzberg. In four of the ten, the drug was found to provide no benefit over placebo—the sponsors had focused on publishing the positive results and hiding the negative ones.

Among the five studies conducted in U.S. patients, three found no drug benefit, and in the other two, no drug benefit was demonstrated at either the 10 mg or 15 mg starting dose. Thus, in five U.S. trials that compared 10 or more doses of vortioxetine to placebo, the drug may have provided a statistically significant benefit over placebo only two to four times. The claim of efficacy, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices concluded, “depended heavily on foreign trials.”

The Institute also found that once vortioxetine was on the market, adverse events reported to the FDA told of a problematic drug. In a 12-month period ending September 30, 2017, there were 45 deaths associated with vortioxetine use, adverse behavioral changes (suicide, self-injury, hostility, and aggression), numerous reports of sexual dysfunction, and the emergence of eating disorders.

Patient Drug News similarly reported a long list of side effects associated with vortioxetine and concluded that the drug provided “little benefit” and had “significant risks.” Meanwhile, the FDA informed Lundbeck and Takeda that they couldn’t state that its drug produced cognitive benefits, as the data didn’t support such a claim.

The money tree

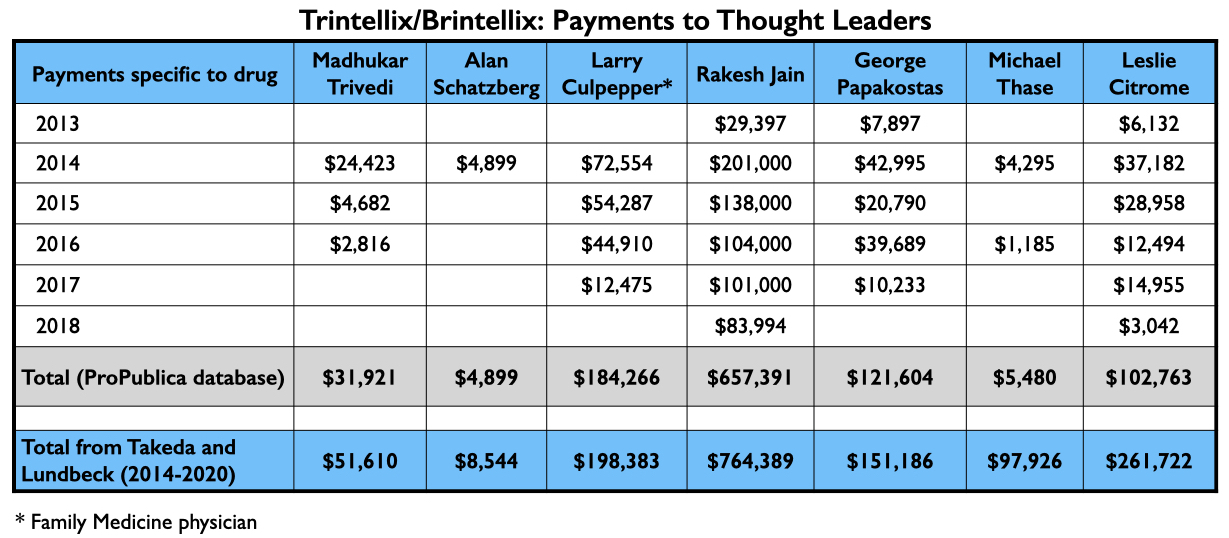

With their various published reports, Trivedi, Citrome, and Schatzberg’s group had served as U.S. “thought leaders” pronouncing vortioxetine as safe and effective, with possible advantages over existing antidepressants. Here is what they were paid by Takeda and Lundbeck for their consulting/speaker services from 2013 through 2018 related to vortioxetine (ProPublica database), and the total amount they received from Takeda and Lundbeck from 2014 through 2020 (Open Payments database):

Rakesh Jain, who was one of the authors on the Schatzberg paper, also appears on a list of the top four speakers paid by Takeda. Here is the flow of money that went to three others for promoting vortioxetine from 2013 through 2018, and the total they received from Takeda and Lundbeck from 2014 through 2020.

While this antidepressant may not have shown much efficacy in clinical trials, it still found success in the marketplace. Medicaid and Medicare paid more than $1.25 billion to the makers of Trintellix/Brintellix from 2014 through 2019, with sales rising each year as Stahl and the other speakers made their rounds.

Rexulti/Brexpiprazole

Otsuka and Lundbeck, which had joined together to bring Abilify Maintena to market, also jointly developed brexpiprazole. The FDA approved it in 2015 as a treatment for schizophrenia and as an adjunct treatment for depression, with the two companies marketing it as Rexulti.

In three reports of pivotal studies of brexpiprazole for schizophrenia, 10 of the 12 authors were company employees. The two non-employees were U.S. psychiatrists Christoph Correll and John Kane.

The published results

The phase III studies were conducted in a population of chronic schizophrenia patients experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms, nearly all of whom were on antipsychotics before the study. After being withdrawn from whatever antipsychotics they had been on, the patients were randomized to one of four doses of brexpiprazole (.25 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, or 4 mg) or to placebo.

In a pooled analysis of the phase III studies, at the end of six weeks those in the 2 mg. and 4 mg. groups had “statistically significant” greater decreases in their PANSS scores than those treated with placebo. Kane, Correll and the company employees concluded that this “meta-analysis of the pivotal studies indicates brexpiprazole 2 mg and 4 mg are effective in treating acute schizophrenia.”

The critique

There are three trials of brexpiprazole to review: a phase II study and two separate phase III studies (no pooled analysis). In all three studies, there is the usual drug-withdrawal group masquerading as a placebo group, and multiple doses of the study drug are compared with one dose of placebo. First-episode patients were not eligible for the trial (which assured that no drug-naïve patients would be in the placebo cohort).

The primary endpoint was reduction in symptoms on PANSS. Even with the biased design, not a single dose of brexpiprazole—in either the phase II study or the phase III studies— came close to providing the 15-point difference that is understood to provide a “minimum clinically important” benefit.

Even in terms of providing a statistically significant benefit, which is a much lower standard, brexpiprazole’s efficacy record was of a marginal sort. In the phase II study, all four doses of brexpiprazole failed to provide a benefit over placebo. The phase III studies compared three doses to placebo: a low dose, a 2 mg dose, and a 4 mg dose. The low dose failed to provide a benefit in both studies, and the 2 mg dose failed to do so in one of the two phase III studies. It was only by pooling the results from the phase III studies that the 2 mg dose climbed into the “statistically significant” category.

In the pooled analysis, the 2 mg provided only a 5.46-point difference in reduction of symptoms compared with placebo, and the 4 mg only a 6.69-point difference. Three studies of brexpiprazole, with a total of 10 doses of the drug compared to placebo—the latter a group composed of chronic patients withdrawn from their antipsychotic medication—and not once did a dosage provide a clinically meaningful benefit.

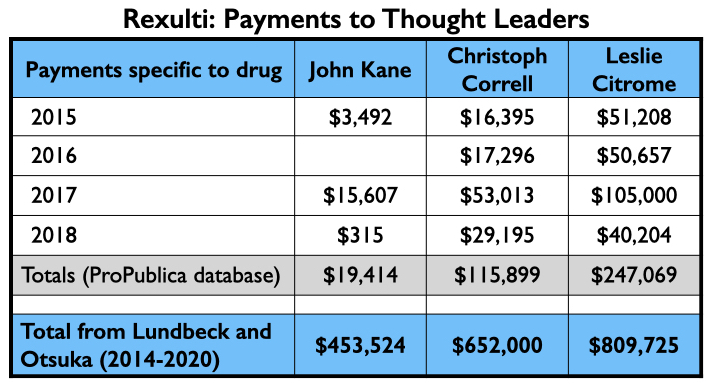

The money tree

After the phase II and phase III results were published, Citrome authored several articles on brexpiprazole, reviewing its mechanism of action, efficacy at secondary endpoints, and so forth, all of which led him to conclude that brexpiprazole “may be particularly beneficial for patients who have struggled with restlessness or akathisia during past medication trials or those who are looking for an alternative medication that is not highly sedating.”

Here is the money that flowed to Kane, Correll, and Citrome for consulting and/or speaker services related to brexpiprazole from 2015 through 2018 (ProPublica database) and the total they received from Lundbeck and Otsuka from 2014 through 2020 (Open Payments database).

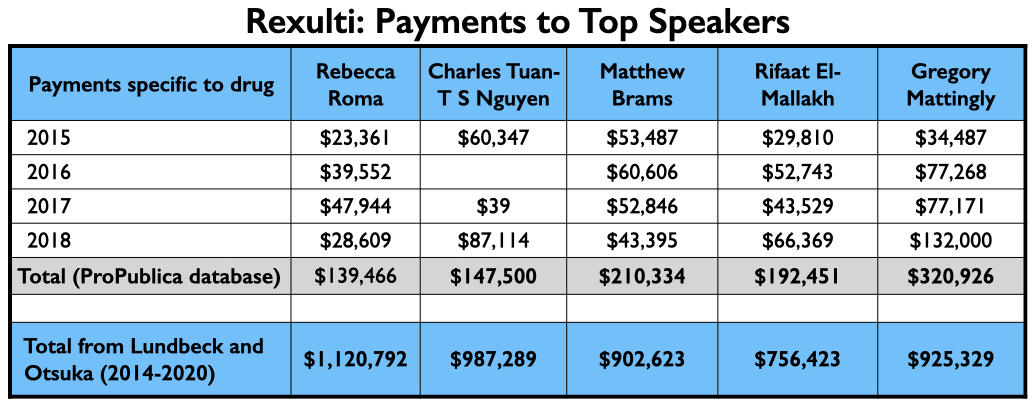

As Otsuka and Lundbeck had previously jointly brought Abilify Maintena to market, they once again regularly employed the same top-earning quartet of speakers: Roma, Nguyen, Brams, and El-Mallakh. However, their top-earning Rexulti speaker from 2015 through 2018 may have been Gregory Mattingly, a psychiatrist who conducted clinical trials for the “Midwest Research Group.”

Here is the money these speakers earned for promoting Rexulti from 2015 through 2018, and the total they earned from Lundbeck and Otsuka from 2014 through 2020.

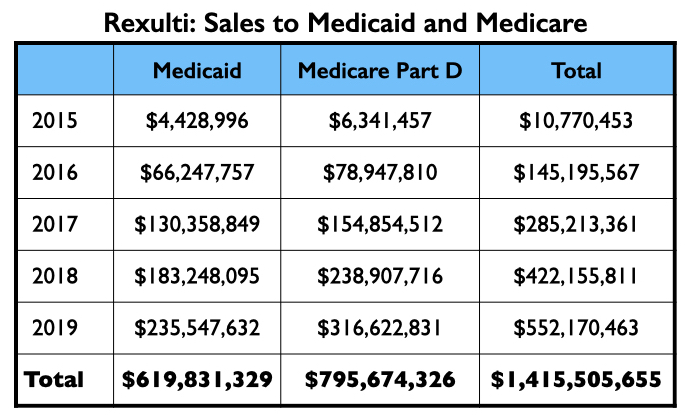

Medicaid and Medicare sales of Rexulti grew steadily from 2015 through 2019, with more than $1.4 billion in total sales.

Vraylar/cariprazine

There were three companies involved in the development and testing of cariprazine: Gedeon Richter, Forest Laboratories, and Allergan. It was approved for treating schizophrenia and mania symptoms in bipolar patients in 2015, and depression in bipolar patients in 2019. Allergan marketed it as Vraylar.

In six reports of pivotal studies for schizophrenia and bipolar, 18 of the 30 authors were employees of one of these three companies. Two of the 18 employees were also patent owners of the drug. Of the 12 non-employees named as authors, 11 disclosed financial ties to at least one of the companies. The one investigator who had no ties, Henry Nasrallah, was subsequently paid $75,823 by Allergan, mostly for speaking services.

The published results

In the three phase II/phase III trials for schizophrenia, patients with a history of “treatment resistance” to antipsychotics were excluded from enrolling. First-episode patients were also excluded. The studies were conducted in chronic patients withdrawn from the antipsychotics they had been on and then randomized to one of four doses of cariprazine or to placebo. In a pooled analysis of the three trials, at the end of six weeks the cariprazine patients had seen their PANSS scores decrease from 6.5 to 9.5 points more than patients in the placebo group (the variability is reflective of scores for the different dosages.) The researchers concluded that “cariprazine was effective versus placebo in all five PANSS factor domains, suggesting that it may have broad-spectrum efficacy in patients with acute schizophrenia.”

The companies also conducted a study of cariprazine for reducing relapse. The chronic patients were first treated with cariprazine, and only those who stabilized and remained stable on the drug for 20 weeks were randomized into the double-blind study. Over the next few months, the relapse rate was twice as high for the drug-withdrawn placebo group than for the cariprazine-maintained group (48% versus 25%). “Long-term cariprazine treatment was significantly more effective than placebo for relapse prevention in patients with schizophrenia,” the authors concluded.

In three pivotal studies of cariprazine for depression in bipolar 1, there were seven comparisons of cariprazine with placebo (at doses of .75 mg, 1.5 mg and 3 mg). In four of the seven comparisons, cariprazine provided a statistically significant benefit, and in the three others it did not. In the four “successful” comparisons, the difference in symptom reduction between drug and placebo ranged from 2.4 to 4.0 points on the 60-point MADRS scale. Cariprazine “was effective, generally well-tolerated, and relatively safe in reducing depressive symptoms in adults with bipolar 1 depression,” the researchers concluded.

The critique

The phase II/phase III trials of cariprazine were similar in design to the brexpiprazole trials: First-episode patients were excluded; multiple doses of the drug were compared with a single dose of placebo; and the placebo group was composed of chronic patients that had been abruptly withdrawn from their antipsychotic medication. In addition, only patients who had previously responded well to antipsychotics were allowed into the trial (e.g., people with a history of a poor response were excluded). The pooled data told of efficacy similar to that of brexpiprazole at 2 mg and 4 mg: The differences on the PANSS scale were statistically significant but fell short of the 15-point “minimum clinically important difference.”

The relapse study was conducted in a select group of good responders to cariprazine. Of the 765 chronic patients enrolled into the study, only 200 successfully stabilized on cariprazine and remained stable for the required 20 weeks before being randomized into the double-blind trial. Only 18 of those randomized to cariprazine completed the 72-week relapse study; the remaining 89 in the drug arm either relapsed, discontinued due to adverse events, withdrew their consent, or were lost to follow-up.

In sum, only 26% of the chronic patients recruited into the study stabilized long enough to enter the relapse trial, and of the 101 then randomized to continued cariprazine treatment, 82% failed to finish the trial. That’s a documented stay-well rate at 72 weeks for the cariprazine-treated group of 3%.

As for the studies of cariprazine as a treatment for depression in bipolar patients, only four of seven dosages provided a statistically significant benefit, and the difference in reduction of symptoms on the MADRS scale between drug and placebo, even in those instances where the difference was statistically significant, was of a marginal sort.

It is also noteworthy that five of the six lead authors of reports reviewed by MIA were company employees. Either one or both owners of the drug patent were listed as authors on five of the reports.

The money tree

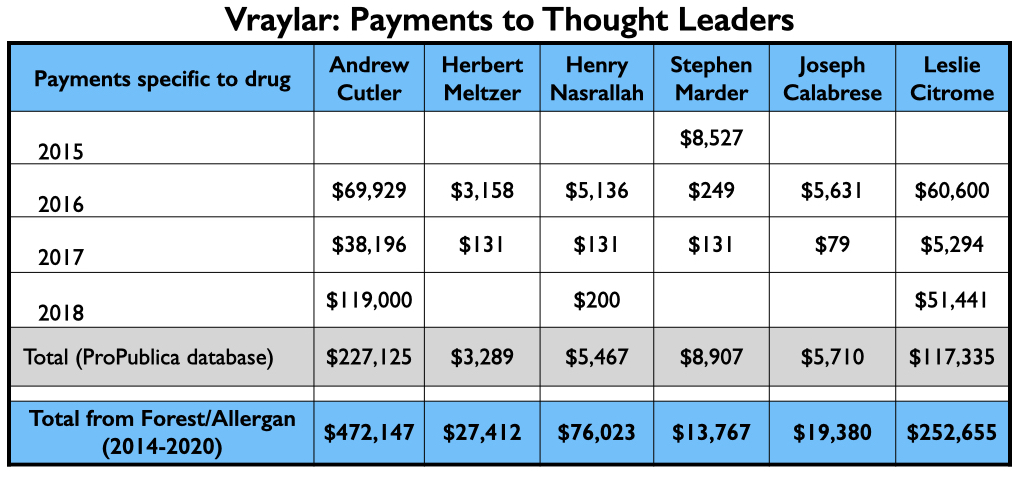

Here is the money that flowed to the five U.S. psychiatrists named as authors on one or more of the six published studies, and to Leslie Citrome, who published 17 articles on cariprazine, including 10 where he was the sole author.

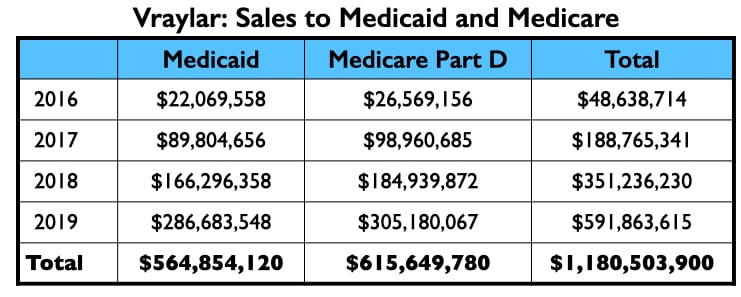

The four psychiatrists at the top of the Vraylar speakers list are all familiar names from the million-dollar club. Medicare and Medicaid sales totaled $1.18 billion during the drug’s first four years on the market.

Aristada/aripiprazole lauroxil

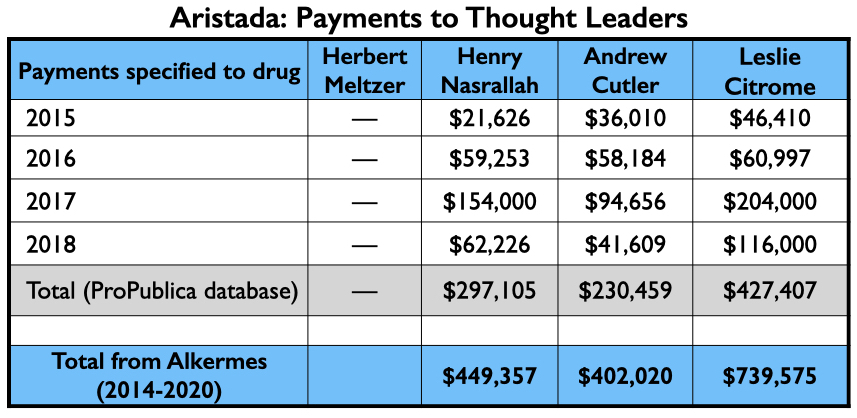

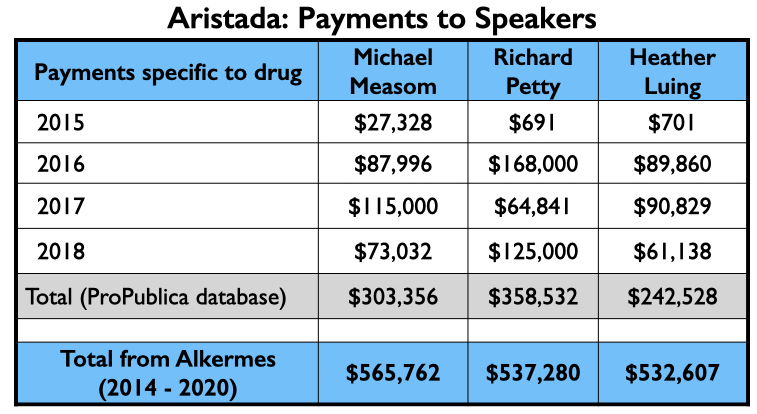

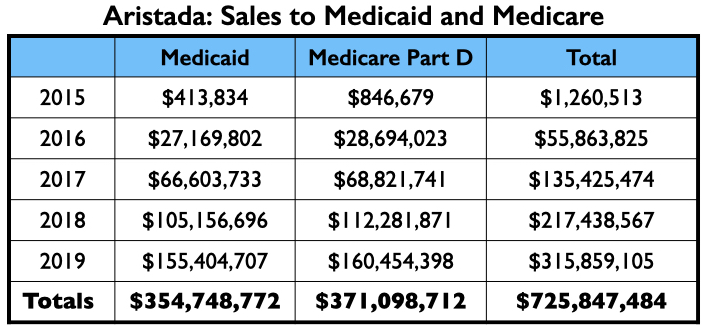

Alkermes obtained FDA approval for aripiprazole lauroxil in 2015, marketing it as Aristada. This was a second injectable form of aripiprazole, touted as being an improvement over the once-monthly Abilify Maintena because it lasted longer in the body.

In a report on the pivotal Phase III study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, eight of the ten authors were employees of Alkermes. The two non-employees were U.S. psychiatrists Herbert Meltzer and Henry Nasrallah. Meltzer was a consultant to Alkermes during the study; Nasrallah was an advisor to the company and on its speakers’ bureau.

The published results

The chronic patients recruited into the study needed to have had a previous “clinically beneficial response” to an antipsychotic. Patients who previously had an “inadequate response to oral aripiprazole” were excluded. After being withdrawn from the antipsychotic medications they had been on, the enrolled patients were randomized to aripiprazole lauroxil or to placebo. Those randomized to the injectable aripiprazole were also given an oral dose of aripiprazole for the first three weeks.

At the end of 12 weeks, the PANSS scores in the injectable group had decreased by 22 points, which was 12 points more than the decrease in the placebo group. “This study demonstrated robust efficacy of multiple doses of aripiprazole lauroxil with a safety and tolerability profile of oral aripiprazole,” Meltzer, Nasrallah, and the company employees wrote. “The clinical profile of aripiprazole combined with the flexibility afforded by novel technology and ability to administer in the deltoid and gluteal muscles may represent a new treatment option for both clinicians and their patients with schizophrenia.”

Leslie Citrome, Andrew Cutler, and Nasrallah, together with four Alkermes employees, subsequently published a further analysis of the phase III data in CNS Spectrums that provided information about “supportive efficacy endpoints.”

The critique

This phase III study had the usual design for an antipsychotics trial: Chronic patients with a history of having responded positively to an antipsychotic were abruptly withdrawn from antipsychotic medication, and then a comparison was made between those who were put back on an antipsychotic and those left in a drug-withdrawal state. The result is almost always the same. The neural pathways in the brains of these chronic patients have adapted to the presence of dopamine-blocking drugs, and so those put back on a drug with this mechanism of action will have a greater reduction of symptoms on PANSS than the “placebo” group.

This design also ensures that the placebo group—since it is a drug-withdrawn group—will suffer frequently from “adverse events.” In this study, the percentage of patients who suffered a “treatment-emergent adverse event” was highest for the placebo group (62.3%), which included such events as insomnia, akathisia, headache, and anxiety. This high incidence of adverse events in the placebo group helps provide a foil for assessing the drug treatment as relatively safe and tolerable. (This same factor can be seen in the studies of brexpiprazole and cariprazine.)

This also wasn’t a trial of aripiprazole lauroxil as a stand-alone treatment. The difference in decrease in PANSS scores between the drug and placebo groups occurred mostly in the first three weeks, when the aripiprazole lauroxil patients were also being treated with oral aripiprazole. Once on the injectable alone, there was little continued decrease in their PANSS scores.

While the 12-point difference in PANSS scores at the end of 12 weeks was statistically significant, it still fell short of the “minimum clinically important” 15-point difference. Indeed, at the end of 12 weeks, the mean PANSS score for the aripiprazole lauroxil patients was 71, which is associated with being “moderately ill.” Only 36% of the aripiprazole lauroxil patients were deemed to have responded to the drug (a 30% drop in PANSS scores), versus 18% of the placebo patients.

The money tree

Here is the money tree for Aristada: payments to the four U.S. psychiatrists who were authors of the two papers; the payments to the top three speakers (other than Citrome, who was an active speaker for Aristada), and the Medicaid and Medicare sales.

Austedo/deutetrabenazine

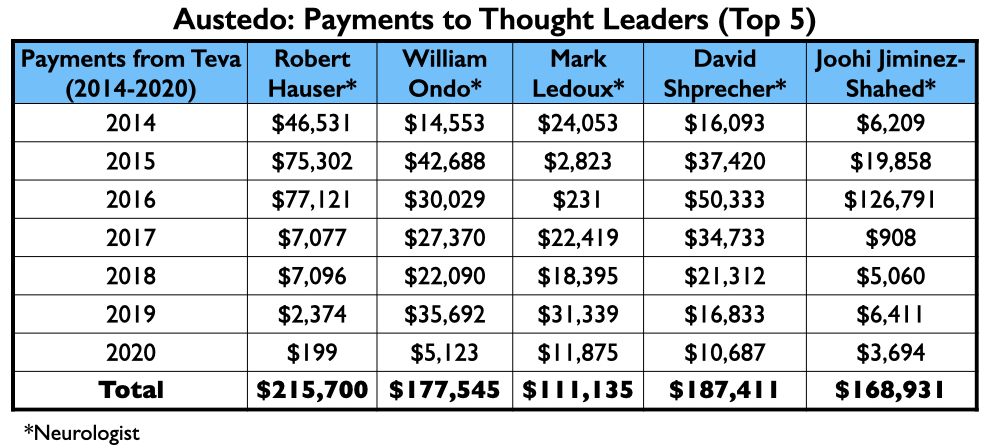

Teva obtained FDA approval of deutetrabenazine as a treatment for tardive dyskinesia in 2017, marketing it as Austedo. The company mostly relied on neurologists to test its efficacy in stilling abnormal motor movements, and then heavily promoted it with psychiatrists who are popular on the speaking circuit.

The published report of a pivotal 12-week study listed 15 authors: two were employees, eight were neurologists paid by Teva as consultants and/or speakers, another was a PhD consultant, and the remaining four were U.S. psychiatrists.

The published results

In the study, patients suffering from tardive dyskinesia were randomized to deutetrabenazine or to placebo. They were allowed to continue taking the psychiatric medications they were on. At the end of 12 weeks, the deutetrabenazine group experienced a drop of 3.0 points on the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), compared with a drop of 1.6 points for placebo, a difference that was statistically significant. “In patients with TD, deutetrabenazine was well tolerated and significantly reduced abnormal movements,” the authors concluded.

The critique

AIMS assesses motor function in seven areas, with scores of zero to four in each domain. A total score of 7 on the 28-point scale tells of minimal symptoms, with abnormal movements “infrequent and not easy to detect.” A total score of 14 tells of “mild” TD—abnormal movements that are “infrequent but easy to detect.”

The mean AIMS score for the patients in the 12-week trial was 9.6, which meant that this study was conducted in a group with minimal to mild symptoms. The 1.4-point difference in reduction of symptoms between drug and placebo, while statistically significant, would not be of “minimum” clinical importance. Researchers have determined that there needs to be at least a 2-point difference on AIMS for it to be clinically meaningful.

In addition, on two other secondary efficacy scales that were used, the Clinical Global Impression of Change and the Patient Global Impression of Change, the differences in improvement between the deutetrabenazine and placebo groups were not statistically significant. Neither the investigators nor the patients, when asked to give their impression of whether they had improved or stayed the same or grown worse on the drug, noticed a difference.

The money tree

Here is the money that Teva had paid the eight neurologists by the end of 2020 for their consulting or speaking services:

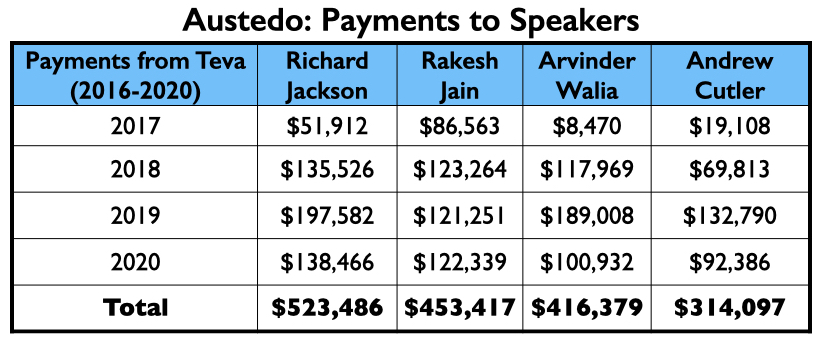

Teva’s speakers list featured four psychiatrists from the million-dollar club: Richard Jackson, Rakesh Jain, Arvinder Walia, and Andrew Cutler.

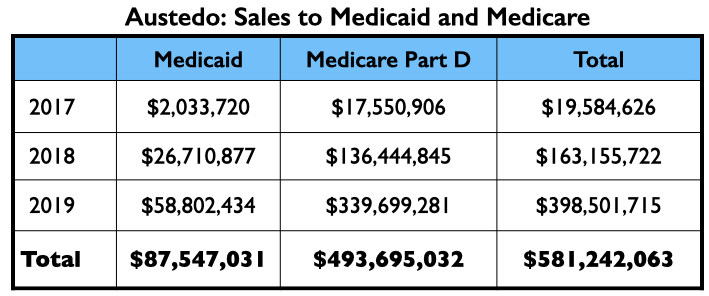

In its first two full years on the market, Austedo generated nearly $600 million in Medicaid and Medicare sales.

In its first two full years on the market, Austedo generated nearly $600 million in Medicaid and Medicare sales.

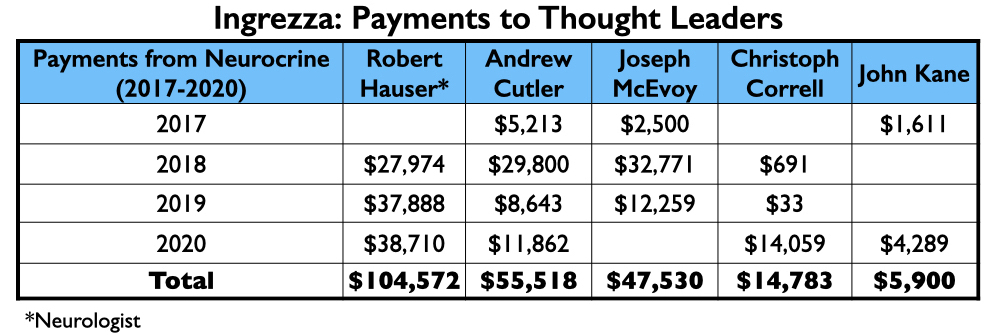

Ingrezza/valbenazine

Valbenazine, which was developed by Neurocrine Biosciences and marketed as Ingrezza, was approved at the same time as deutetrabenazine as a treatment for tardive dyskinesia.

Four of the nine authors of a phase III report on valbenazine were employees of Neurocrine. Four others had financial ties to the company, including the lead author, neurologist Robert Hauser.

The published results

In the phase III study, two doses of valbenazine were compared with placebo. The 80 mg dose led to a 3.2-point drop in symptoms on the AIMS scale at six weeks; the 40 mg dose a 1.9-point drop. As the placebo group in this study didn’t improve (.1 point decrease in symptoms), the 3.1-point difference between the 80 mg dose of valbenazine and placebo was more robust than the results in the deutetrabenazine trials. “Once-daily valbenazine significantly improved tardive dyskinesia in participants with underlying schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or mood disorder,” the researchers concluded.

The critique

The patients in this study had a mean AIMS score of 10.0, and thus it was a group with minimal to mild symptoms. While the AIMS score at both doses told of a statistically significant benefit, only the 80 mg. dose exceeded the two-point difference for a “minimum clinically important difference.”

On a second endpoint, the “Clinical Global Impression of Change—Tardive Dyskinesia,” there were no significant differences between either drug dose or placebo at week six. This is an assessment by clinicians of the overall change in the clinical status of the patients, ranging from very much improved to very much worse on a scale of one to seven. The fact that there was no significant difference on this scale reveals that the investigators, in this double-blind trial, didn’t notice a clinical difference in the two groups at either dose.

The money tree

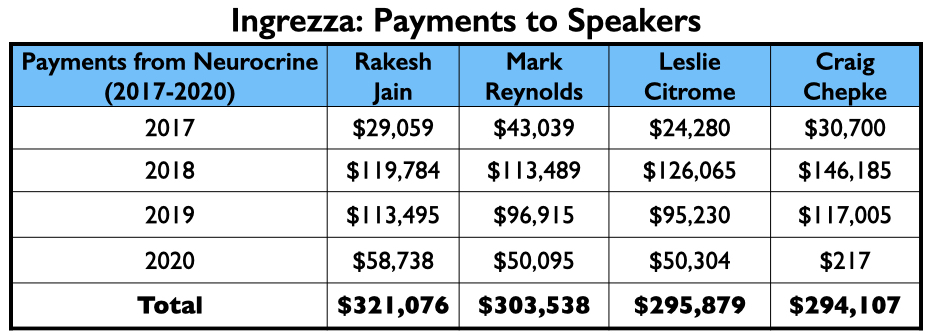

Neurocrine’s payments to its thought leaders were generally less than what the thought leaders for the other six drugs approved from 2013 to 2017 were paid.

However, the top four on the speakers’ list included three from the million-dollar club (Citrome, Jain, and Reynolds), and a fourth who didn’t miss that mark by much, Craig T. Chepke. Both Citrome and Chepke authored articles on valbenazine, with Chepke’s published in CNS Spectrums.

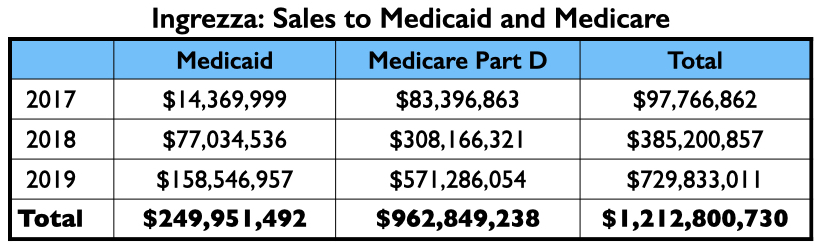

Ingrezza had a fast rise in sales, generating more than $1 billion in Medicaid and Medicare payments in its first two full years on the market.

The Bottom Line

The Open Payments database makes it possible to discover the amount of pharmaceutical money paid to individual psychiatrists throughout the testing and marketing of new drugs. What this review reveals is that money flows to the consultants and advisors who help the companies design their trials and author articles on the results; it flows to those who publish reviews and further analyses of the new drug once the trial results are published; and it flows to those who serve on speaker bureaus.

While the $340 million that pharmaceutical companies paid psychiatrists from 2014 to 2020 may have provided individual psychiatrists with substantial earnings, it is a small expense for the drug companies. The payments fuel the telling of a narrative, wrapped in the scientific gauze of “double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized trials,” of drugs that are safe and effective for a particular condition, with possible advantages over existing drugs. As can be seen in the Medicaid and Medicare payments for the seven approved drugs, this narrative then generates billions in sales.

What this critique also reveals is that the testing of psychiatric drugs is a charade. It is a process designed not to inform, but—as long as the drug makes it past FDA review—to produce a commercially valuable soundbite. These studies were riddled with elements of bad science.

The studies of the four antipsychotics all used inclusion-exclusion criteria to select a group of potentially “good responders” to the drugs, and in several instances, selected for a group that had stabilized well on the study drug for several months before randomization.

The exclusion of first-episode patients from such trials is also of note. If antipsychotic naïve, this is the very group that could provide a real test of whether an antipsychotic reduced symptoms better than placebo. A Cochrane review concluded in 2011 that there is, in fact, no good evidence that antipsychotics are effective in first-episode patients. By excluding such patients from their trials and only enrolling chronic patients, the drug companies can hope they will be spared such failure.

Trials of antipsychotics, of course, have nearly always relied on placebo groups composed of patients abruptly withdrawn from such medication (or withdrawn over a seven-day period). Here is the moral foil for judging this practice: If a psychiatrist in everyday practice abruptly withdrew a chronic schizophrenia patient from antipsychotic medication, and then left that person untreated for weeks and months, that would be seen as malpractice. Yet, that very act of clinical malpractice stands at the heart of randomized controlled trials of antipsychotics, and everyone turns a blind eye to this fact and pretends the withdrawn group reflects the “untreated” course of schizophrenia. The king, so to speak, is completely naked, and yet the psychiatric community, when reciting “evidence from double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials,” pretends that the king is dressed in resplendent scientific garb.

The most remarkable aspect of the clinical trials of brexpiprazole and cariprazine is that even with the biased inclusion/exclusion criteria, and even with the use of a drug-withdrawn placebo group, these two drugs still failed to provide a “minimum clinically important difference” in symptoms on the PANSS scale over placebo.

A failure to provide a clinically meaningful benefit was also evident in the phase III studies of Aristada and Austedo. Those two drugs also missed the mark, and so did Abilify Maintena in the maintenance trial in schizophrenia. That makes five of the seven approved drugs that did not provide a “minimum clinically important” benefit in clinical trials. As for Ingrezza, only one of two doses reached that standard, and even with the dose that did, ratings by clinicians and the patients on whether they had improved or worsened didn’t tell of a difference between the valbenazine and placebo groups.

Yet, none of these critiques made it into the abstracts of the published reports for these six drugs, nor into the conclusions drawn by the authors. There was no discussion of a lack of a meaningful clinical benefit; instead, over and over again, the authors told of drugs that had proved “safe and effective” in “randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.”

As for the trials of vortioxetine, Otsuka and Lundbeck published only those that told of a positive finding. The failure of this drug in U.S. trials was kept hidden from the public, and this brings up another bad-science element: How can the results possibly be trusted, given that company employees are authoring the reports and deciding which results should be published? It is possible that reviews of FDA data for the other six drugs would also turn up negative trials that were never published, and that if such findings were known, the risk-benefit ratio for the six would appear even worse.

All of this tells of a process that serves a commercial end, rather than providing society with an honest scientific assessment of a drug’s risks and benefits, and whether the benefit is clinically meaningful. The “framework” of science is utilized to mislead—rather than inform—the public.

As a commercial pursuit, however, it produces this bottom line: American taxpayers spent $9.3 billion on these seven drugs from the time they were approved through 2019 in the form of Medicaid and Medicare payments, and based on the 2019 numbers and growth rates in sales, taxpayers spent another $5 billion in 2020.

And that is the “bottom line” when you follow the money: There is money that flows to individual psychiatrists and to the drug companies, and at the heart of this commercial enterprise is “science” designed to deceive.

"industry" - Google News

September 18, 2021 at 05:00PM

https://ift.tt/3kkQ44z

Anatomy of an Industry: Commerce, Payments to Psychiatrists and Betrayal of the Public Good - Mad In America - James Moore

"industry" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2RrQtUH

https://ift.tt/2zJ3SAW

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Anatomy of an Industry: Commerce, Payments to Psychiatrists and Betrayal of the Public Good - Mad In America - James Moore"

Post a Comment